Nick Dinardo challenges their rights being violated by Correctional Service Canada

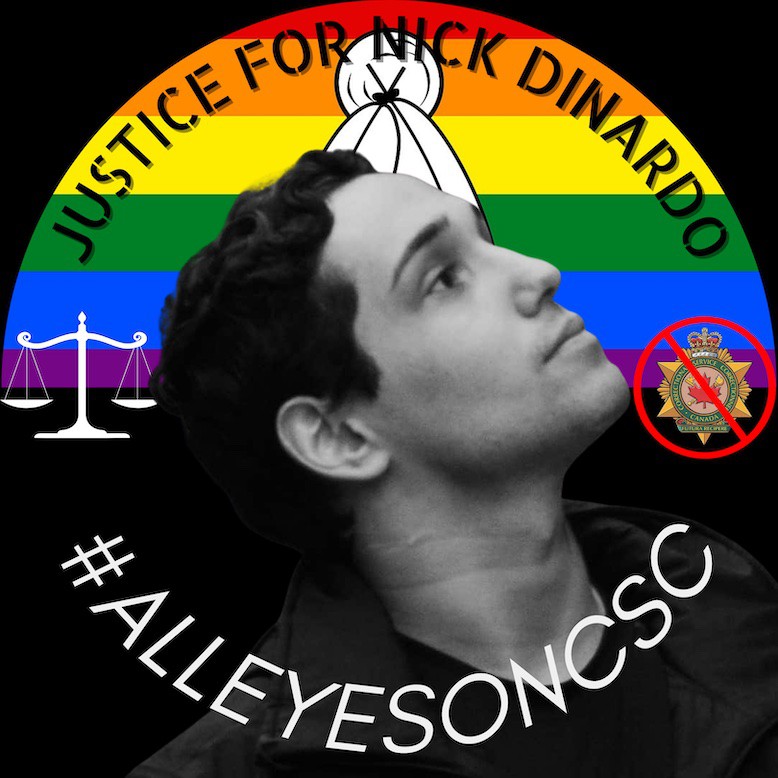

Art by Rowan Hynds, Nick Dinardo's cousin

Dinardo has filed multiple human rights complaints, none of which, they claim, have led to any significant disciplinary measures for the correctional officer involved in the incidents. Now they are putting together a Gladue report to present to court. Gladue reports are ordered by courts to consider the circumstances of Indigenous people living under settler-colonialism. Gladue reports require judges to offer alternatives to jail for the individual in question and consider a person’s community’s perspective and the laws, practices, customs, and legal traditions of their Nation, or the Nation where the alleged offence took place.

Dinardo is a member of Piapot First Nation, located approximately 50 kilometres north of Regina. They are a survivor of the Canadian governement’s Indian Day Schools which, like the residential schools Dinardo’s parents attended, abused Indigenous children and attempted to erase Indigenous languages and cultures. Dinardo suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and a variety of other mental health issues.

“An ongoing issue”

Since their first brush with the correctional system at 18 years old, Dinardo has faced countless instances of discrimination and abuse by correctional officers, especially during their current sentence. Dinardo has been verbally and physically abused and denied medical treatment, among other abuses of power by correctional officers and correctional institutions across Canada. While some of the mistreatment occurred before they came out as transgender, their treatment became significantly worse after coming out as Two-Spirit.

According to Dinardo, the incident that prompted their current charge only occurred due to being wrongfully arrested in Regina for a crime in which they were not involved.

“I ended up beating the charges I got arrested on, but while waiting to go to trial, I incurred eight years for institutional assault,” says Dinardo.

“They were calling [my gender] a disorder, something that could be cured or medicated or fixed. It’s [...] degrading.”

They explain that they were placed in a correctional facility with inmates that they did not feel safe around. They say that an inmate instigated a fight with them, and Dinardo defended themself.

“[The prosecutors] said I stabbed him even though there was no weapon found because there was never a weapon. I didn’t stab him. There [were] all these [details] that didn’t add up,” says Dinardo. “I feel as though [I’ve had] an ongoing issue with the RCMP throughout my life.”

“I was charged with assault […] but after a few trials, the [man involved] didn’t want to show up. He didn’t want to co-operate at trial,” says Dinardo. “My lawyer was asking him why [he was] pursuing these charges and he said that he wasn’t co-operating because he didn’t want to do it. The guy ended up getting new charges and the RCMP said that they would get him into programming and treatment to get out of jail if he co-operated and pressed charges against [me].”

Dinardo then spent around two and a half years in isolation.

“[I've had] an ongoing issue with the RCMP throughout my life.”

In December 2017, CSC put into place new policies to prevent discrimination on the grounds of gender identity or expression. These policies require CSC to accommodate gender-diverse individuals for programs, searches, clothing, and related areas.

This includes accommodating gender-diverse individuals by placing them in facilities that align with their gender identities, as opposed to their gender markers or biological sex. These policies, while required, were frequently not applied with Dinardo.

As Dinardo is Two-Spirit and transfeminine, they applied for placement at women’s institutions numerous times throughout this sentence. However, multiple reports concerning Dinardo’s application stated that they were a man and required male programming, causing Dinardo to be denied placement in a women’s facility.

Dinardo specifies that these reports also refer to their gender status as “gender identity disorder,” an outdated, transphobic diagnosis that equates trans identity with mental illness.

“I’m Two-Spirit. But [the staff member] said the same thing each time: ‘You are a man.’”

“They were calling [my gender] a disorder, something that could be cured or medicated or fixed. It’s [...] degrading,” explains Dinardo. “Other psychologists and psychiatrists had actually told me that that’s wrong and that the person who said that should be educated.”

Art by Rowan Hynds, Nick Dinardo's cousin

“A lot of stuff has happened through the last three years. I went from penitentiary to treatment centre, back and forth, then was shipped all the way to [the] Kent Institution [in B.C]. This is where a lot of my other suffering started because they cut me off of my [ADHD] medication,” says Dinardo.

Dinardo was then shipped from B.C. to an institution in New Brunswick where they lost a dangerous amount of blood after engaging in self harm. A program officer convinced them to seek medical attention, where they received a life-saving blood transfusion.

Dinardo was then involuntarily transferred to Port-Cartier Correctional Institution in northern Quebec. They were told that they would be able to communite with English-speaking staff and access appropriate programming, but Dinardo received neither. In addiont, they were transferred in 2020 in the height of the pandemic, when many inmates including Dinardo were being kept in isolation to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Dinardo reports being kept in isolation for 23 hours a day.

“[I've had] an ongoing issue with the RCMP throughout my life.”

Despite the blood transfusion, Dinardo’s blood levels were still critically low and they feared that they might die if they tried harming themself again. “Sometimes I don’t know how close I am. I could just black out and die,” worries Dinardo. “I felt like I was wanting to hurt myself. I get [that way] in isolation. Officers tell me to try and talk about stuff before I start reacting violently toward myself, so that’s what I was trying to do,” says Dinardo.

Dinardo asked a correctional officer to speak to the unit manager, who responded that he would let the unit manager know when he was done his rounds. But instead, he came back with five other guards.

“They kicked me into my cell and my leg got caught in the door. I came back out of my cell and stood there. That’s when they all brought me to the ground and [one guard] kicked me into my cell and started doing something […] called ‘joint manipulation.’”

Dinardo explains that “joint manipulation” is when guards pop prisoners’ joints out of their sockets and then pop them back in to cover up the evidence. “I thought I was never going to use my arm again,” says Dinardo.

“The cut from earlier on my arm was pretty much pouring blood. These people would have actually killed me.”

While Dinardo sought medical attention immediately afterwards, it was not until eight days later on June 7, 2021 that Dinardo was taken to a hospital. Doctors took X-rays of their arm, but not of their shoulder, which was also injured.

“[The doctor] said to me that it was definitely a fractured bone and that he usually puts people in casts. But he thought that I didn’t need it and that a brace would do. I tried to explain to them that my arm wasn’t always going to be in that brace position because I get handcuffed behind my back or shackled in a body belt,” Dinardo remembers. “My arm was in excruciating pain. But [the doctor] didn’t care at all.”

Then, on July 12, 2022, their arm was reinjured by a different correctional officer while returning from another appointment to have X-rays done on their shoulder.

Further harm

At the end of August, 2022, Dinardo was transferred to Millhaven Institution in Ontario. A month later, they were again abused by guards. Distressed by the incident, Dinardo cut their arm and they had to go to the hospital to have the wound treated. Upon their return, guards placed them in an observation room and asked them to strip for a pat down.

Only women guards are allowed to search Dinardo, but none were present at the time. Around 10 male guards surrounded them insisting that Dinardo strip in order to be searched, but Dinardo refused to be searched by the male guards. Being intimidated by the guards stressed Dinardo and they broke open their wound.

The guards dragged Dinardo behind the main jail facility where a guard verbally assaulted them causing Dinardo to fear for their life.

“The cut from earlier on my arm was pretty much pouring blood. These people would have actually killed me,” shares Dinardo. “Their protocol was to either bring me to the shower or try to do first aid on my arm to stop the bleeding. But what they did was completely out of line.”

Dinardo recounts that the guards then dragged them behind the main jail facility where a guard verbally assaulted them causing Dinardo to fear for their life. “One guard just kept saying stuff to me like ‘you’re disgusting, you’re not a woman,’ things like that. But one of the things he said that stuck with me was “You want to be a bitch, I’ll treat you like a bitch” while yanking on my arm,” says Dinardo.

Following this, Dinardo was dragged to the medical jail. They describe the incident as “the most traumatizing experience” of their life.

“We want to encourage people to act and let the government, the parole board, and Correctional Service Canada know that people are watching and that they’re going to have something to say about what comes of this case.”

At this point, Dinardo stayed in their cell most of the time, even once they were transferred between jails. In March 2022, they were released to a halfway house run by the Salvation Army in Victoria, B.C. The halfway house was not the one they wanted to be placed in – they had wanted to be placed in the Bill Mudge House, also in Victoria.

“The director of Bill Mudge was talking to me before I got out and recommended that I go to his halfway house because they’ve helped transgender people with their transition and helped them move on. They’re good. It’s a lot more support,” notes Dinardo.

“I thought I was going there but [...the officers] said that I had to be fully vaccinated. I found out later that it was a lie.” Dinardo had been unable to be vaccinated due to their blood transfusions.

“He said that he wasn’t pointing fingers at anyone, but he wasn’t allowed to take me and work with me. No one told me any of this, I didn’t have a clue,” explains Dinardo. “I [feel] like my release was botched right from the beginning.”

At the halfway house, they were required to do a urine analysis test for a parole officer. The officer insisted that Dinardo do the test in front of a man, despite them being transfeminine.

“She was saying you’re a man, so you will be getting tested by one. So, I explained three times that it’s not about the anatomy of the body, it’s about what you feel, your self-identity. It’s part of my culture. I’m Two-Spirit. But she said the same thing each time: ‘You are a man,’” recounts Dinardo.

Dinardo insists they did their best to make their placement at the Salvation Army halfway house work. Despite the degrading experience with the parole officer, there was an upside to staying at there: they could see their cousin Rowan Hynds and Hynds’ wife, Whitney.

“I went to see Rowan as soon as I could,” shares Dinardo. “We hadn’t seen each other for over five years.” Unfortunately, their reunion only lasted a half hour because the halfway house required Dinardo to check in with staff an hourly basis during their stay. But the hourly check-ins made it difficult for them to see Hynds to catch up and work on Dinardo’s legal cases together.

Even though Dinardo was released to the halfway house, CSC had no intentions of letting them walk free, insist Hynds and Dinardo. Staff made numerous accurations against Dinardo and wrote them up several times for things like missing curfew. But Dinardo and Hynds explain that it was the staff who dropped Dinardo off at the wrong location for a medical appointment and Dinardo had no clue where they were. The halfway house also failed to accomodate Dinardo’s Kosher diet for multiple days of their stay.

“I [feel] like my release was botched right from the beginning.”

“All of this stuff is a huge human rights violation and I fully intend on putting a human rights complaint against the Salvation [Army...]. A lot of stuff that happened there in those three weeks and it was really hard not even being able to eat properly. I’d have to stay up late, literally all night, just washing dishes and cooking my food just so I could eat,” Dinardo shares.

Dinardo stayed at the halfway house for three weeks before they were arrested after getting into an argument with another resident after a misunderstanding over cigarettes. The other resident told Dinardo they were worried about being arrested.

“I said something about him not having to worry about me. I wasn’t going to get him sent back to jail, I almost got stabbed there. We started arguing some more and [he] called the cops on me,” Dinardo explains.

Dinardo was in their room when cops arrived and arrested them. They remember the experience was “traumatizing.”

Seeking justice

Dinardo was then placed in Kent Institution in B.C., where they are now working on compiling a Gladue report with help from Hynds.

Hynds believes the states needs to be held accountable for the abuse Dinardo suffered in the prison system and that the first step is sharing what happens behind prison walls, so Hynds started the campaign “All Eyes on CSC.” Hynds posted a video about the campaign to their TikTok account, @gothdyke420, after Dinardo was rearrested in May 2022. The video currently has over 352,000 views.

“I don’t think any of us were equipped to deal with alone,” admits Hynds. “I’m so grateful [for the support].”

The campaign has made a huge difference for Dinardo. “There was a day I was so stressed that I was going to cut myself and I just thought about some of the things people have said online. It kind of hit my heart,” shares Dinardo.

Hynds has received several messages from strangers all over the world who want to join the campaign. The support has helped them feel less overwhelmed and alone in their advocacy for their cousin. “I don’t think any of us were equipped to deal with alone,” admits Hynds. “I’m so grateful [for the support].”

“We want to encourage people to act and let the government, the parole board, and Correctional Service Canada know that people are watching and that they’re going to have something to say about what comes of this case. They can’t just keep doing these things in the dark anymore. People are watching,” says Hynds.

You can show your support for Nick Dinardo by visiting koji.to/alleyesoncsc and by following Rowan Hynds @gothdyke420 on TikTok.