Searching for family roots leads to connections between Métis and Doukhobor

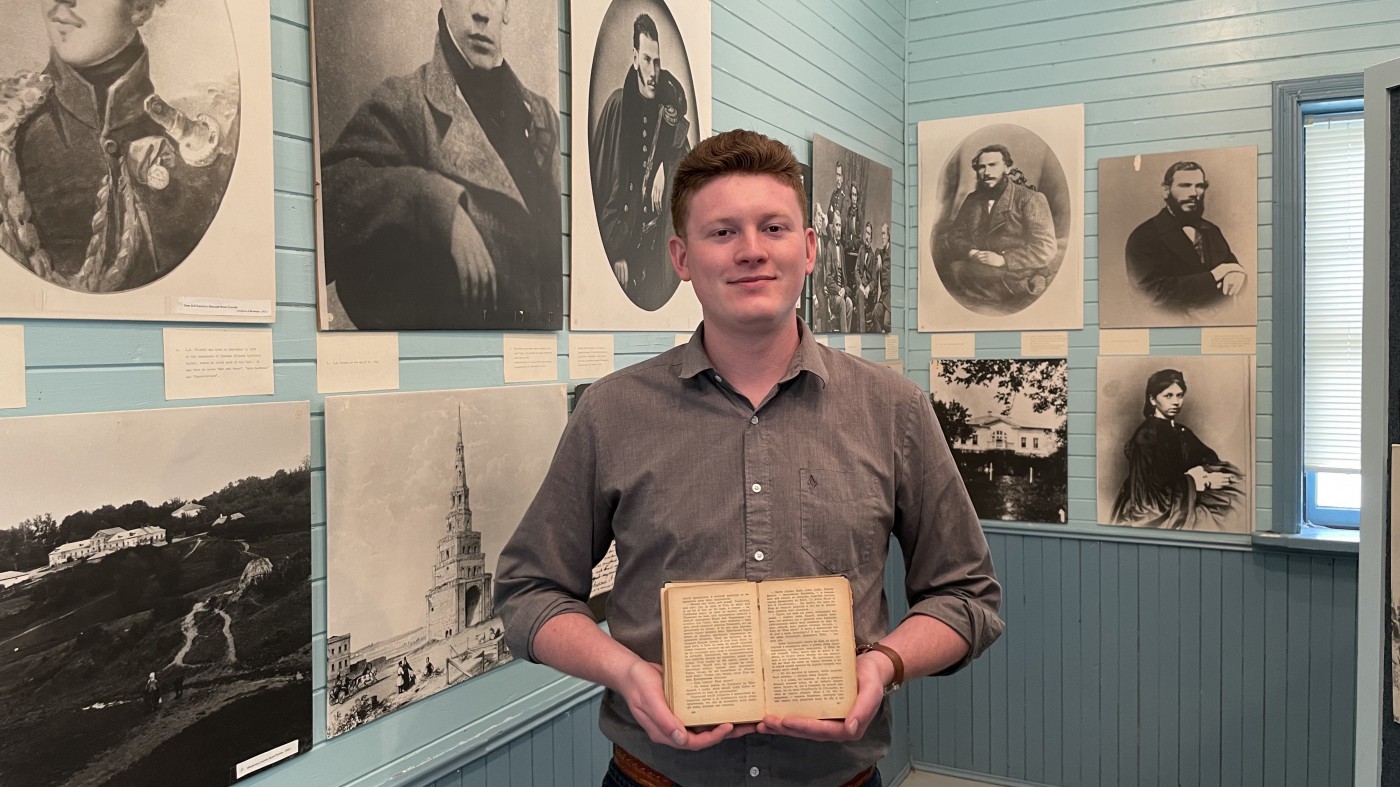

Mason Hausermann at the National Doukhobor Heritage Village, holding a book by Russian author Leo Tolstoy. Hausermann says that Tolstoy’s social status and “pacifist ideology made him a valuable ally to the Doukhobors. Tolstoy (among other individuals) was instrumental in pleading to foreign countries and governments on behalf of the Doukhobors after the harsh persecution they faced under the Tsarist Regime.” Photo submitted by Mason Hausermann

In Verigin, SK, as Mason Hausermann makes preparations for the National Doukhobor Heritage Village’s celebration of Peter’s Day on June 29, he finds himself reflecting on his own roots. As a person of Métis and Doukhobor descent, he works not only to educate others on history, but also to further his own knowledge and understanding.

Through his work in uncovering the branches of his own family tree, Hausermann has discovered some substantial family ties, ranging from Russian Doukhobor ancestry going back generations to being connected with newfound relatives across Canada through the discovery of a link to prominent Métis leader Cuthbert Grant Jr.

“I think being able to tell these stories that they thought were lost is very important,” says Hausermann, reflecting on the hundreds of visitors he’s met at the Doukhobor heritage site. “Being able to tell these individual stories, these narratives that maybe aren’t told for a number of reasons, it goes into a lot of aspects of decolonization and trying to say that there’s different ways to tell these stories.”

“I’ve been able to help people find their ancestors. I’ve been able to show people the ship logs, for example, and being able to show, ‘hey, this is the ship your family came on,’ specifically when talking about Doukhobors, it just makes the job worth it.”

The Doukhobors, Russian for “spirit wrestlers,” are a Russian religious group built on “toil and peaceful life,” explains Hausermann.

“I think it’s an ideology that we should all share now,” he continues. “It’s this idea that you work hard, but you live a peaceful life. “

Pacifism plays a major role in Doukhobor heritage and culture. In 1895, the Burning of the Arms saw the Doukhobors destroy their rifles and other weapons to protest their involvement in the Russian military. This pacifist policy, and the Russian government’s response to it, is what brought the Doukhobors to Canada.

“Being able to tell these individual stories, these narratives that maybe aren’t told for a number of reasons, it goes into a lot of aspects of decolonization and trying to say that there’s different ways to tell these stories.”

“This idea of the Doukhobors being distrustful because they were doing their own thing, this didn’t line up with how the Czar wanted all his subjects to be loyal, so them not wanting to fight due to their pacifist beliefs meant that they wouldn’t serve in the Czarist army, which you had to back in the day, right?” explains Hausermann. “So [the Czar] would send Cossack soldiers to assault them and force them [to fight], and so that persecution caused a lot of death. Many of my family members would have been killed in these pogroms against them, and then those who did survive were sent into exodus.”

Looking for a new home free of discrimination and political turmoil, many Doukhobors found themselves moving to Canada in the early 20th century.

“As soon as the Doukhobors came, the [Canadian] government offered them land, in Saskatchewan specifically, and as soon as they came to Saskatchewan, they weren’t given any oxen, they weren’t given any tools, they weren’t giving any winter clothing, they only had what they could take from Russia,” says Hausermann.

“When they came to Canada, and I think this has a lot to do with the Red Scare of the time and this distrust of Slavic peoples, just horrible racism against them.”

According to Hausermann, the hardships faced by Doukhobours in Russia and Canada are not well-known, since many refrained from keeping proper documentation and records for fear of reprisals from both governments. They feared that any information could be used against them by Russia, even overseas, whereas in Canada they were wary of keeping detailed records for fear of their pacifist communities possibly being subjected to military conscription. Much of what Hausermann knows has been uncovered through his own historical research and archival work.

“Through the multitude of artifacts and research materials provided at the National Doukhobor Heritage Village, I was able to map out the story of my ancestors,” he said. “Census records illustrated to me which villages they would have lived in [in] Russia, and ship logs showed their flight from persecution.”

His research has uncovered new information both on his own Doukhobor ancestry and that of countless visitors, but he is eager to inform all members of the public, regardless of their ancestry, about the hardships the Doukhobors suffered over a century ago.

“I really like to focus on that, because I feel like people don’t understand that this is a group who went through so much that they had to literally escape to a different country, and I think it’s a very inspiring story,” says Hausermann.

In spite of the adversity they faced in their new home, Hausermann says they succeeded. “Doukhobors were able to break the land by themselves. They were able to survive.”

“The men worked on the railroad, they worked on the highways and worked on the grain elevators,” he elaborates. “This idea of literally building Saskatchewan to what it is today off the backs of the Doukhobors, I think that’s very inspiring.”

This legacy is something that Hausermann and his colleague strive to depict at the National Doukhobor Heritage Village, a National Historic Site of Canada.

“We try to show the sense of village, of a home,” says Hausermann.

The location features Doukhobor buildings and thousands of artifacts, many of which belonged to prominent Canadian Doukhobor leader Peter Verigin, the namesake of Verigin, SK. His life of influence and leadership came to an end on October 29, 1924, when a train car exploded, killing him and seven others.

No definitive explanation exists for the explosion, which Hausermann classifies as an assassination, as it nears its 100th anniversary.

“I think these narratives just show a tragic mistake, a misguidedness of how people can abuse power to hurt people.”

Political and social factors are all possible motives – possible Russian distrust of the Doukhobor community and its Westernization, coinciding with Joseph Stalin’s rise to power in the preceding years, or the prevalent xenophobia throughout Canada – with the Canadian and Soviet governments, the Ku Klux Klan, and organized crime syndicates operating in Saskatchewan all being among many potential suspects. Hausermann has dedicated a substantial amount of time to researching the alleged assassination.

“I think these narratives just show a tragic mistake, a misguidedness of how people can abuse power to hurt people,” he says, including the assassination as one of many examples of discrimination and violence against the group.

The Doukhobor lifestyle, as depicted at the Village, plays a prominent role in Hausermann’s life.

“This idea of being peaceful, working hard and being one with nature, I think in this day and age [is more relevant than ever with] problems such as deforestation and pollution, global warming. I think it’s good to look back at groups who’ve lived in connection with nature, not using it.”

These ideals hearken back to Hausermann’s Métis heritage: through his tireless research of his ancestry, he has been able to make some significant discoveries, including that Josephte Grant, sister of prominent Métis leader Cuthbert Grant Jr., is his relative.

Through his construction of a detailed family tree, Hausermann was able to connect with a living relative in Manitoba: Métis author and advocate Alexandria Anthony who, like Hausermann, has been hard at work diving into her own ancestry.

“I’ve been on this journey for, I guess, 20-plus years or so,” says Anthony.

“It all started when I was a little kid. I was brought up in a Métis household. My grandparents were Métis, so I was brought up in the culture, I guess, without even realizing it,” she continues, saying she had not recognized their use of the Michif language until later on.

“My grandfather was a trapper, so I thought every kid did that. I didn’t think it was weird or odd,” she says. “There were kids going to Disney World and Disneyland […] and I thought, ‘Hey, man, I’d rather go on the trapline with my grandfather than go on some kind of a kids’ ride’ because I was born into the life, and being Métis without even realizing it.”

Anthony says she has been familiar with the hardship associated with being a Métis person in Canada since childhood.

“I have dark features, Indigenous features, and my mom would always say ‘when you go to school, tell people you’re French because we don’t want you to get beaten up,’” she says. “Even to this day, my mom is in her 80s and she has a hard time saying that she’s a Métis person. It’s all about trying to hide. We’re literally hiding in plain sight.”

“I’d rather go on the trapline with my grandfather than go on some kind of a kids’ ride’ because I was born into the life, and being Métis without even realizing it.”

Anthony and Hausermann’s Métis ancestry inspired both to undertake their respective journeys of historical research, aiming to uncover the truth about their roots – for Anthony, her journey of Métis advocacy kicked off when she discovered that she was related to 19th-century Métis leader Cuthbert Grant Jr.

“I remember my mom telling me ‘you’re related to some famous Scottish guy’ and I thought, ‘Okay, well, what does that mean?’” she explains. “So as I got older, she began to tell me the story about Cuthbert Grant Jr. and his role.”

According to Anthony, the leadership of Cuthbert Grant Jr., who was deemed a National Historic Person by the Government of Canada in 1972, coincided with the beginnings of Métis nationhood.

“The Battle of Seven Oaks, or as we Métis call it, the Victory of Frog Plain […] happened in 1816, so that was really the first time that Métis asserted their rights and fought for their rights to exist, to provide for their families.”

The battle, which had its 208th anniversary celebrated by the Métis community on June 19, was the result of escalating fur trade disputes between the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company, which employed Grant Jr. and other Métis. After the firefight and victory, Grant Jr. raised the Métis flag, one of the first recorded instances of such a thing happening.

“I think once I found out that I was related to him, and then I found the colonial perspective on his life … even growing up, going to high school or middle school, we were never taught anything about Métis people.”

“We’ve had to fight for our existence, we’ve had to fight for our rights and we’re still fighting for land.”

With over 20 self-published books to her name, Anthony decided to take her education on Métis heritage into her own hands while making a difference.

“Nothing was ever said about Cuthbert Grant, Métis people, and I thought ‘no, this doesn’t sit right for me,’ because I’m a Métis person and it’s like I don’t even exist. People have to understand that Métis people played a key role in the foundations of Canada as a country, and we’ve had to fight for our existence, we’ve had to fight for our rights and we’re still fighting for land.”

These sentiments, and the unique perspective with which she approaches her life and work, are shared with fellow historian Hausermann, who, as an avid environmentalist says that “through these ways of knowing that both the Indigenous and European sides of my family have, I think these are ways we can learn to better the planet.”

Hausermann is committed to educating the public on history while continuing to further his knowledge of his own roots.

“The big thing is finding connections and meeting people,” says Hausermann on the process of finding distant ancestors and living relatives across Canada and even the world. “I think being able to say, ‘Hey, no, these stories matter’ is quite important […] finding this connection to my Métis family is quite important, too. My grandmother, who at first was forced to feel ashamed due to the racism she experienced, was able to say no [to racism].”

“So I feel like these [Doukhobor and Métis] ideas are very important to how I identify as a person.”

Hausermann only had his Métis status recognized in 2021, which he says is a sign that it’s never too late to start tracing one’s origins and learning more about one’s heritage.

“[My work] gives me that connection to my heritage, and I’ve really been able to tell these stories that people never heard,” he said. “Telling stories about people who had their voices taken from them, people who worked hard all their life and weren’t able to have their stories told, fills me with a great sense of pride.”