Decarbonized, democratized, decolonized

Saskatchewan’s Just Transitions Summit

Twelve years. That’s how long we have to reduce our carbon dioxide emissions by 45 per cent from 2010 levels, in order to stop the impacts of climate change escalating from moderate destruction to extreme devastation. This timeline is according to a report by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), released October 8.

Five days later, Ryan Meili, leader of the Saskatchewan NDP, announced the Renew Saskatchewan plan to lower our province’s emissions by providing loans for “clean energy installations or retrofits for homes, farms, businesses, industry, municipalities and reserves.” The plan says loans would be repaid with the savings on power bills, and promises to “drop your power bills right away, and in a few years get them down to almost nothing.” They liken it to Tommy Douglas’ Rural Electrification Program of the 1950s, which had to first persuade farmers to get on board with the plan, and then install overhead lines and in-home wiring. It took 17 years to bring electricity to roughly 76 per cent of farms.

We have 12 years.

Renew Saskatchewan will not get us far enough fast enough. Per capita, Canada is one of the highest emitters of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the world, and while most provinces managed to reduce their emissions between 2005 and 2015, those reductions were almost completely offset by drastic increases in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Responding to the IPCC’s call means reducing our emissions from the 2010 level of 70 megatonnes per year to 34.5 megatonnes within 10 years. Why does Renew Saskatchewan fall so short of this target? And what kind of plan could get us there?

Why does Renew Saskatchewan fall so short of this target? And what kind of plan could get us there?

On October 27 and 28, the Just Transitions Summit brought 150 people together in Regina, on Treaty 4 territory, to “discuss the possibilities and pathways for transitioning Saskatchewan’s economy to renewable energies” in a way that is just, particularly for workers and Indigenous peoples. I was involved in organizing the event along with Emily Eaton, associate professor of geography at the University of Regina and researcher with the Corporate Mapping Project.

Target the biggest emitters

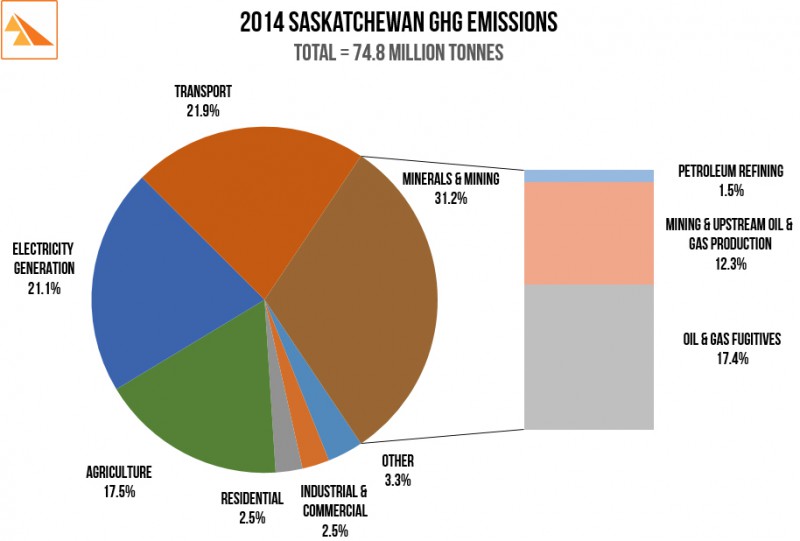

On the first day of the summit, Eaton, along with Simon Enoch of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, broke down Saskatchewan’s emissions by sector, noting the two sectors emitting the most greenhouse gases (GHGs) – mining and transport – are also the ones that have seen emissions rise over the last decade.

Of Saskatchewan’s GHGs, 17.4 per cent are oil and gas fugitives alone – “pure waste” such as “gases that escape at the wellhead or spill out of pipelines, or are vented and flared into the atmosphere,” Eaton explained. “No viable strategy to reduce emissions in Saskatchewan can neglect the [oil and gas] sector and, to a lesser extent, transportation.” Yet aside from declaring support for carbon pricing, the NDP has provided no indication of how they will stifle supply-side oil production, or tackle the emissions of resource extraction industries.

Courtesy of SaskWind

Renew Saskatchewan will work mainly to reduce the small fraction of GHG emissions that come from electricity generation for residential homes and small businesses. But Eaton and Enoch explained that the largest consumers of electricity are big power accounts like potash and uranium mines. “In fact,” Eaton noted, “just 35 customers use 45 per cent of the electrical power in the province.”

“Industry” is on the list of those eligible under the NDP’s plan. But will the availability of government loans make a difference for the province’s biggest consumers of electricity? Are Cameco and Nutrien chomping at the bit to put up solar panels, and the only thing stopping them is their inability to get a loan? Not likely. Renew Saskatchewan promises to get the power bill down to almost nothing, but that’s less of an incentive for big power account holders who are, in some cases, already paying less than SaskPower’s cost of production.

For those of us paying the full electricity rate from smaller budgets – homes, farms, businesses, municipalities, and First Nations – the plan could make a difference. And the thought of going solar by simply continuing to pay the power bill is exciting – at least for those of us with a desire to do so. But voluntary, individual actions will not achieve a 45 per cent reduction within the next 12 years. As Eaton explained, “if every individual resident in Sask reduces their emissions to zero from their cars, their homes, their electricity consumption – it would only amount to a total reduction of between 10 and 12 megatonnes of GHG emissions. […] So while individual emissions are an important piece of the puzzle, they’re not the source of Saskatchewan’s high emissions, and we have to plan for how to reduce emissions substantially by industry.”

Are Cameco and Nutrien chomping at the bit to put up solar panels, and the only thing stopping them is their inability to get a loan? Not likely.

Surely the NDP knows that individual, voluntary actions won’t be enough. So why, then, does their leading climate action plan focus solely on this? Why not propose policies requiring reductions in the highest emitting sectors? Is it to build public support? Is it to avoid offending industry? Is Murray Mandryk’s headline in the Regina Leader-Post right in saying that Meili is walking the “fine line in selling green policy to public and party”?

Yens Pedersen, the SK NDP’s Environment critic, acknowledges, “It is not a comprehensive climate change strategy and does not pretend to be – instead, it seeks to shift the focus of the public climate change conversation from threats and costs to opportunities and benefits as a means of building support and momentum for the full transition we know is needed. The full platform will be in the works as we move closer to the 2020 election.” By then, we’ll have 10 years left.

We don’t have time for plans that walk the line. We need a plan that can transform the line into a circle, show people a reason to step inside, and use our collective power to challenge the industries telling us that our lives can only get worse, not better, without them in charge.

Democratize the transition

At the summit, presenters and participants spoke with passion about the urgent need to move away from fossil fuels, but also with excitement about the possibilities that such a massive shift presents. Enoch sees the transition as a chance “to imagine a new economy that is not only sustainable, but perhaps more radically democratic and hopefully more just.” And in order for the transition to succeed, he says, “it has to transform systems of power in this country as much as it has to transform systems of energy.”

“We have seen that rational, detailed, technical arguments are not usually winning the day, no matter how grounded in logic or science,” Enoch continued. “To me, this means that transition is equally a political problem as it is a technical problem. And I mean political in the original sense of the word about power – who has it, who doesn’t. Who gets to make decisions. Who has decisions foisted upon them.”

“It has to transform systems of power in this country as much as it has to transform systems of energy.”

Workers in the fossil fuel industry certainly know what it’s like to have decisions foisted upon them. Oil companies decided to prioritize shareholders during the industry’s downturn, and 20,000 workers were laid off in 2015. The federal government has decided to phase out coal by 2030, leaving coal workers in Estevan and Coronach wondering what will be next.

Climate Justice Saskatoon (CJS), one of the groups that presented at the summit, interviewed some of the workers in these two municipalities as part of a project to help “bridge the gap between urban environmentalists and coal-producing communities.”

Hayley Carlson, an organizer with CJS, speaks about the interviews on the most recent episode of the group’s weekly radio show, From the Ground Up. “The sentiments being expressed were very similar to my own,” she notes. “They didn’t feel like decision makers were listening to them […] and they weren’t reflected in decisions that were being made. We feel like that, I think, consistently.”

“So we’re sort of bypassing the [political] decision-making element by just going directly to the communities and having a conversation. Of course we’re not going to agree on everything […] but maybe we’re building capacity as a group across Saskatchewan to take more effective action on these issues.”

Decolonize the transition

If rural settlers in the fossil fuel industry and urban settlers in the environmental movement are feeling unheard, what about Indigenous peoples?

Michelle Brass of Indigenous Climate Action said at the summit, “Indigenous peoples contribute the least to GHG emissions around the world, yet our communities are impacted the most and often the first, and we’re not at the table when it comes to the federal, provincial, or municipal levels of government in developing climate policy. So Indigenous peoples have been forced to the streets basically to take our messages and get our voices out there.”

“Indigenous peoples contribute the least to GHG emissions around the world, yet our communities are impacted the most and often the first.”

Other speakers said that a just transition means not “leaving people behind.” Brass responded, “Indigenous peoples have not been left behind, we’ve been completely shut out of our home territories. [… For] those of us who are rooted in ceremony, who are taking our guidance from the land […] it’s not about being left behind. We want to live an Indigenous lifestyle in our home territories. And it is the sustainable lifestyle.”

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples asserts their right to do that. The spirit and intent of the Numbered Treaties, which form the basis of settler society’s presence on this land, oblige us to honour the sovereignty of Indigenous nations and to live well together on the land they are sharing with us. As the NDP develops its platform over the next two years, will they propose a climate action plan that lives up to these obligations?

Su Deranger, who attended the summit, is doubtful. “Don’t talk to me about NDP,” she tells me afterwards, in an interview. “I’m a refugee from a trapline in Northern Saskatchewan where we were violently kicked out of our own traditional land so they could mine uranium up there. It was 1979, and the NDP was in power. They even said that ‘legally we were trespassing but morally we weren’t’ – whatever that doublespeak is. They also signed leases for the tarsands to come in, and everything else. So they’re not innocent. And they can give all the talk they want and look good before an election, but I’ve seen what the NDP does. I don’t have faith in any political party. And as long as we’re in that matrix, we’re not going to change.”

Not only does Deranger not see a political party as a viable leader for a just transition, she sees them as part of the apparatus of colonial power that needs to be dismantled in order to achieve it. Deranger is a member of Mother Earth Justice Advocates (MEJA), a non-partisan group in Regina that is based on the recognition that social and climate justice depend on the adherence to the inherent rights of Indigenous peoples and the Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth. MEJA’s Declaration for a Better World calls for a move from “Governance to Autonomy” with autonomous systems of “decentralized collective power and authority at the community level.” She is encouraged by the work of the Zapatistas and the Indigenous community of Cherán in Mexico, which recently banished political parties. “The only thing the parties have done is divide us,” says Salvador Ceja, Cherán’s communal lands commissioner.

“I’m a refugee from a trapline in Northern Saskatchewan where we were violently kicked out of our own traditional land so they could mine uranium up there. It was 1979, and the NDP was in power.”

It’s tempting to say that those of us living in Saskatchewan will need to overcome our own deeply entrenched divides before we’ll be able to achieve a just transition to a low-carbon economy. But what if a just transition isn’t the result of overcoming our divides? What if working together toward a just transition will be the way we overcome them?

At the summit, Enoch noted, “Transition has to be able to build a base of power that can challenge those that would wish to obstruct or delay change.” In the absence of political leadership that is willing or able to do that, organizations like Mother Earth Justice Advocates, Indigenous Climate Action, Climate Justice Saskatoon, and all of the other groups which took part in the Just Transitions Summit are building momentum from the grassroots up.

To learn more about how you can support the momentum, contact SaskForward on Facebook or by email: [email protected]