Remembering those who died in Sask’s psychiatric institutions

Saskatchewan Provincial Mental Hospital, Weyburn, in 1921. Photo courtesy of the Soo Line Museum.

In the summer of 2004, Geoffrey Reaume and Ed Janiszewski walked through waist-high grass and overgrown branches at the Lakeshore Psychiatric Hospital’s cemetery in Toronto. They were looking for graves. Reaume is a scholar of Mad history and Janiszewski once worked at the psychiatric hospital where thousands of people labelled with psychiatric disorders and intellectual disabilities lived from 1889 to 1979. The cemetery, once on the outskirts of Toronto, became prime land for a new highway – and the gravesite had not been maintained despite provincial laws that should have safeguarded it. There, Reaume and Janiszewski discovered that 1,510 patients had been buried at this location, 1,356 of them in unmarked graves.

Finding thousands of bodies near psychiatric institutions in Canada is heartbreaking, but it’s not unusual. Many residents of asylums died while in medical care, some from medical neglect, abusive staff, and poor living and working conditions. Others died of old age and diseases.

In August 2021, inspired by these activists and enraged by the discovery of unmarked graves at Indian residential schools, I set out to look for the institutional graveyards in my home province of Saskatchewan.

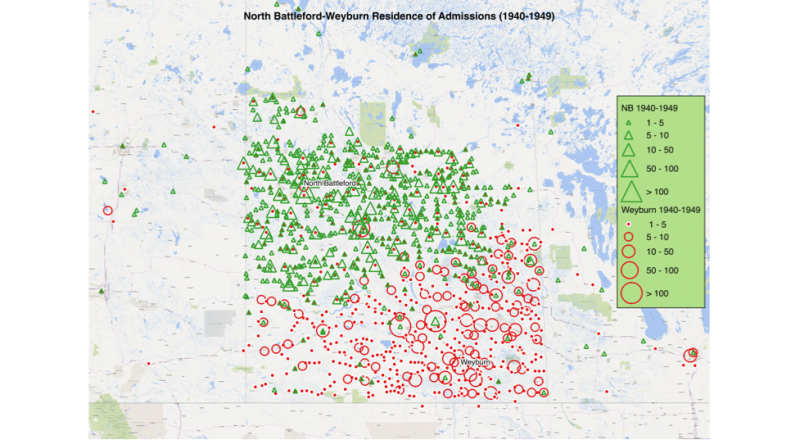

In Saskatchewan, the two main provincial asylums were established in North Battleford in 1914 and Weyburn in 1921, in the province’s northwest and southeast regions. The provincial government selected these locations so that residents wouldn’t have to travel far from their homes. Patient admission files, however, reveal another story. For the first few decades after the hospitals opened, superintendents insisted that families not visit patients, claiming it could slow their recovery. While some patients came from unsafe or dysfunctional settings, the policy was widely applied and it effectively cut ties between patients and their spouses, siblings, parents, and extended family members. With time and distance, repairing these broken relationships became increasingly difficult. Much like other psychiatric facilities from the turn of the 20th century, Saskatchewan’s psychiatric institutions were major employers. This era was the peak of institutionalization, a period that reinforced the power of institutional facilities to segregate, classify, govern, and potentially change how patients reintegrate into modern society.

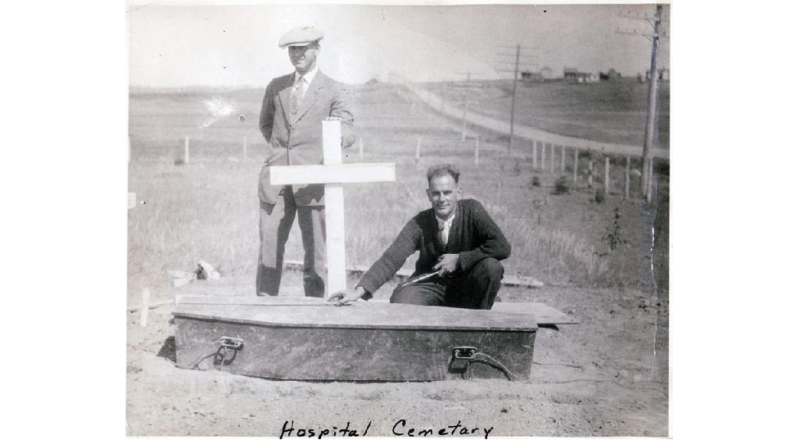

A cemetery at the Sask Hospital, Weyburn. Photo courtesy of the Soo Line Museum.

I visited North Battleford with some friends and former staff from the field of mental health services. We went to the new Saskatchewan Hospital North Battleford, a large multiplex centre with nearly 300 beds for psychiatric patients, located beside a demolition site where the first provincial asylum (or mental hospital) once stood. Thousands of people lived and worked in that mental hospital from its opening in 1914 to its closure in 2018. Between the old grounds and the banks of the North Saskatchewan River, a large tree garden surrounds a war memorial honouring the fallen soldiers from the area. Across the river at the old site of the Battleford Industrial School is a former Indian residential school. We followed a path past a shrine onto a hillside with the graveyard of children from the residential school. The recent headlines had attracted more visitors than usual, and they had adorned the graves with teddy bears, ribbons, and orange T-shirts – a reminder that every child matters.

For the past two decades, I’ve studied the history of psychiatric services, medical experimentation, and deinstitutionalization, with a focus on Saskatchewan. In this article, I discuss psychiatric institutions within the larger historical context of institutionalization in Saskatchewan and reflect on the politics of commemoration for people labelled with psychiatric disorders and intellectual disabilities. I hope that by doing so I can draw attention to some of the experiences of institutionalized people.

Some politicians and scholars suggest that the proliferation of institutions in the late 19th and 20th centuries was a symbol of progress; establishing schools, legislatures, prisons, and hospitals represented a sign of modern development. In Saskatchewan, our legislative buildings, first psychiatric hospital, provincial university, and penitentiary were built within a decade of the province’s founding. Designed to inspire awe and to illustrate the strength of the state to govern and manage its citizens, institutions became a critical feature of nation building, or in this case, building the province. For many communities, the opportunity to host one of these institutions came with a certain degree of prestige. It brought people into the region and created employment. But, as the headlines about residential school graves remind us, the era of institutionalization also had a darker side.

Map by Erika Dyck as part of research funded by the SK Health Research Foundation on admissions to Saskatchewan psychiatric institutions.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries in Canada and internationally, these kinds of institutions were filled with people considered disabled, disordered, defective, or who otherwise exhibited difficulty fitting into the modern economy. Claudia Malacrida’s book on this topic explores a facility in Alberta that housed people with intellectual disabilities who were considered “feebleminded” and who refer to life in the institution as a “special kind of hell.”

The number of people who were institutionalized far outpaced the capacity to house them, and most of the goals of “rehabilitating” and “curing” patients were replaced with administrative objectives that went hand in hand with warehousing society’s unwanted. For example, patients were put to work farming, sewing, woodworking, cleaning, and cooking, which asylum staff claimed would help rehabilitate them by teaching them discipline and new skills. But over time it became clear that this forced labour was a cost-saving mechanism for institutions because patients weren’t paid for their work.

Isolation and segregation were a central component of institutionalization. In some cases, people admitted into these custodial facilities spent the rest of their lives within the walls and gardens of the asylum. The institutions’ remoteness made it difficult for families to visit, causing institutionalized people to become estranged from their kin and making it costly for families to have their loved ones’ bodies and effects returned after they died. According to hospital records, concerns about expenses, for both families and the institution, overwhelmed competing concerns about connecting with next of kin. In some cases, neighbouring communities resisted the inclusion of psychiatric patients in local graveyards, further necessitating specific hospital graveyards. Asylum graveyards became a regular feature of these institutions.

Graveyards were sometimes adjacent to the asylums and other times located farther away on the large expanses of land provided to these facilities by provincial governments. Although there are exceptions, the graveyards I visited in Weyburn and North Battleford were often unmarked. The cemetery at Weyburn was in part a direct response to the mayor of Weyburn rejecting burials for patients in the community’s local graveyard. North Battleford maintained three graveyards while it was in operation.

In the 1960s, many people began questioning the utility of psychiatric institutions. Vocal critics formed an anti-psychiatry movement in Europe and North America. Invasive therapies – including, notably, the lobotomy, a surgery that typically severs connections in the brain’s prefrontal cortex – revealed a kind of desperation in psychiatry that appeared barbaric. These critics joined forces with reformers to usher in an era of deinstitutionalization, which picked up pace in the 1970s. Hospital administrators moved thousands of psychiatric patients out of custodial institutions during this period and it seemed the institutional experiment had run its course. For some, this moment introduced a new phase: transinstitutionalization – moving people from one institution into another, like jails, nursing homes, or facilities for people labelled with cognitive and behavioural disorders. For others, the move meant shifting into halfway houses, group homes, or other semi-independent living spaces. Some people slipped between the cracks, ending up homeless or in other unstable living conditions.

As institutional populations shrank or at least scattered, large custodial facilities often fell into disrepair. Some hospitals simply closed wings; maintenance often fell short. Urban centres encroached on the hospital grounds, especially in areas where these facilities had been perched on land that was now coveted for its proximity to urban amenities or natural features like rivers and vistas that had once provided a natural boundary to keep people inside institutional walls.

Large-scale psychiatric facilities seemed to have outgrown their original purpose. Some, like Weyburn and North Battleford, were bulldozed. Others were given facelifts, like the once Gothic-looking Toronto Psychiatric Hospital, which was transformed into the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, now more resembling a mall than a hospital.

My colleagues and I visited the North Battleford facility, which opened its doors in 1914 to Saskatchewan’s first psychiatric patients. Walking the grounds with former staff, we were directed to three graveyards. The first one was a short drive from the old hospital site. We parked on the side of a road next to an unmarked parting in the bush. We walked along a path until we came to a gate. The site was freshly mowed and surrounded by a barbed-wire fence. A cairn with no markings sat at one end. We walked the area, searching for markers and finding only a handful: a few older markers with numbers and a newer one that appeared to have been placed recently, perhaps by family members seeing as it stood apart in detail and ornamentation.

The North Battleford facility's first cemetery. Photo by Erika Dyck.

The map provided to us by the new hospital staff indicated two other sites. We drove along the grid road following these instructions until we came to the second site. This one was beautifully set on a hillside overlooking the North Saskatchewan River. It was enclosed by caragana bushes and a small gate. Its relatively private and beautiful location seemed to have attracted other visitors. Remnants of bonfires, broken glass, and garbage greeted us at the entrance.

The North Battleford facility's second cemetery on the banks of the North Saskatchewan river. John and Alma Elias are seen visiting the site. Photo by Erika Dyck.

A numbered gravemarker at the second cemetery. Photo by Erika Dyck.

Inside the gates was a stone cairn, similar to the one at the first site. This site was perhaps newer than the first. Graves seemed to be organized in rows, according to the divots on the ground and the inconsistent markers representing some of the graves. Some markers had only a number. A few had more elaborate carvings including names and dates. We took in the view. We spoke about the lives of people who had lived and died in the Provincial Mental Hospital and then set off to see the last site.

The third site involved a short walk up a rutted dirt road that intimidated us city drivers. Arriving at the entrance, a large stone cairn greeted us with words to guide our visit: “within the confines of this cemetery lie the immortal remains of 742 patients of the Saskatchewan Hospital North Battleford who were laid to rest between 1914 and 1955.”

A stone monument at the entrance to the third cemetery. Photo by Erika Dyck.

We entered a tree-lined alley with large fields on either side. A maintenance crew was enjoying a coffee break as we arrived. We asked how often they mow this area, to which they replied that they are contract workers and weren’t certain how often this was done, but this was their first time doing this work. Their response caused us to raise our eyebrows – we wondered whether this contract was a response to the recent news of unmarked graves found at nearby Indian residential schools.

Like our Toronto colleagues, we found very few markers in these large fields. Gently digging in the sod, we recovered lines of numbered markers in some areas, while an entire field seemed completely unmarked. We quietly walked through this space, each of us reflecting on what it meant to bury 742 patients. Were there ceremonies? Did this space ever enjoy visitors? When were the stone markers built at the entrances?

Our day trip to the graveyards of the Provincial Mental Hospital left us reflective and perhaps a bit agitated. As we ate our lunch, we shared our reflections with one another and contemplated the meaning of all of these unmarked graves. We wondered why no one seemed to be upset about the lack of memorialization. We questioned whether deaths at a psychiatric hospital were commemorated with any ceremony or gathering of staff and fellow patients to mark the passing of lives lived in these institutions. We also wondered how many people knew about these graveyards at all and whether there might be public interest in helping to recover these sites with markers or information about the hundreds or even thousands of people buried in Saskatchewan hospital sites.

The last site visit took us across the river to the old Government House, which was the seat of the government of what was then known as the North-West Territories (now Alberta, Saskatchewan and the Northwest Territories) and later home to Oblate priests. Here we saw two graveyards. The first had impressive, erect stones at the head of each grave, enclosed within a small fence to commemorate the Oblates who ran an Indian residential school and died in the area. Walking further along a tree-lined path, we encountered a stone shrine cut into the side of a hill. Beyond this feature, perhaps 200 yards farther, was a small iron fenced-in area with a large stone cairn. As we approached, we could see teddy bears, slippers, dolls, and ribbons resting on the fence. Inside were marked stones and a plaque identifying the children who had died while in care of the Oblates at the residential school.

My intention in writing this is not to directly compare the graves of institutions, but rather to encourage us to think about the legacy of this age of institutionalization and the many lives that were lost, and perhaps forgotten, in the name of nation building. Many patients and their families put their trust in a set of institutions that were ostensibly designed to restore life and function or to provide education. Walking these sites with former employees was a poignant reminder of the many people who genuinely believed in institutions’ missions of support but who are now outraged and discouraged by how these lives continue to be forgotten.

As older institutions are removed from the landscape – bulldozed, in the case of the two provincial mental hospitals in Saskatchewan – we might also reflect upon the ongoing capacity for institutions to shape lives and deaths, whether they are hospitals, jails, long-term care facilities, or the foster care system. During the pandemic, people living within these institutional contexts faced greater restrictions than most, as ties were further severed with family members and communities. Experiences from COVID-19 should encourage us all to interrogate the delicate balance between care and restriction that exists within these institutional spaces and continue to question who is best served by these facilities.

Thanks to John Elias, Alma Elias, Tim Greenough, Letitia Johnson, and Laurene Wilson for visiting these sites in August 2021 and for their contributions to this article.