Regina’s 92-million-dollar problem

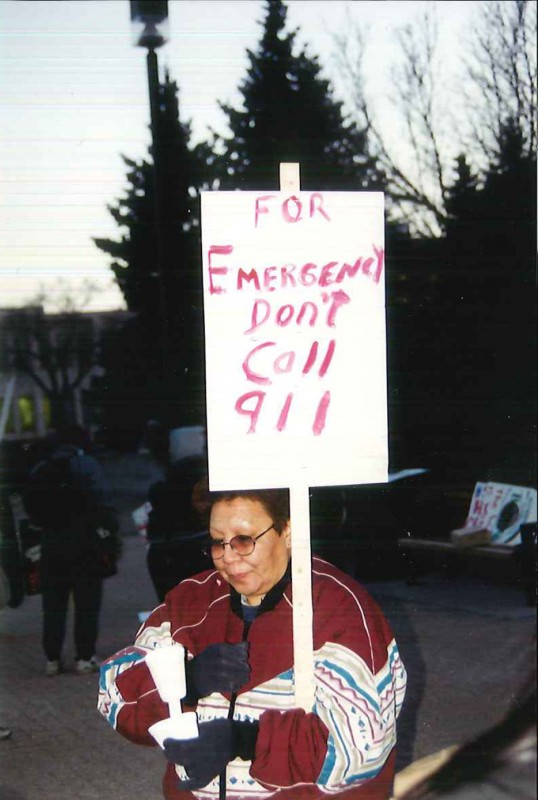

A rally against police brutality in Regina in 2000. The rally appears to have been in response to the deaths of two Indigenous men, Rodney Naistus and Lawrence Wegner, near Saskatoon in 2000. Both froze to death on the outskirts of the city – deaths reminiscent of the practice of “starlight tours.” During starlight tours, police officers would arrest Indigenous people, drive them out of the city, and abandon them there in the middle of winter. Photos from the _Briarpatch_ archives, by Elsie Beechie.

Every year in Saskatchewan, thousands of people have interactions with law enforcement, and every one of those interactions has a cost. Sometimes the price paid is small – just the time and money spent for a pair of officers to check on a home where a family pet has tripped the alarm system. Other times – twice in 2019 – the price paid was someone’s life. At least one victim reportedly suffered from mental illness, and in both cases the victims’ families questioned why officers opened fire rather than using rubber bullets or a Taser. Police-involved shootings like the ones that took the lives of Lucien Silverquill and Geoff Morris are uncommon – although they become statistically more likely when victims are Indigenous or Black. But their seriousness provokes a deeper question: why is law enforcement responding to mental health and social problems at all?

“Policing is the primary response to social problems,” says Jeff Shantz, an organizer and professor of criminology at Kwantlen Polytechnic University in B.C. And even when no one is injured or killed, the social and financial costs of prioritizing law enforcement responses are enormous. “Policing eats up 20 to 30 per cent of a municipality’s budget,” Shantz explains, something that is true in Saskatchewan, where 20 per cent of the budgets of the province’s two largest cities go toward funding their police forces. “Instead of putting money into services that benefit working-class people, they amp up the spending on security,” asserts Shantz, a practice that leads to a vicious cycle wherein a lack of mental health care, anti-poverty initiatives, and addictions treatments leads to an increased crime rate, which is used to justify a ballooning police budget, which necessitates more cuts to the programming needed to end the cycle.

When looking at the differences in funding between law enforcement and the kinds of alternative services that exist, the imbalance is striking. The Regina Police Service (RPS) received nearly $88 million in the city’s 2018 budget, a number that has since risen to $92 million. By comparison, Mobile Crisis Services – which provides emergency support to people suffering from mental health crises, domestic violence, addictions, and more – received a $136,350 grant from the city in 2018, a number that held steady in 2019. Mobile Crisis fielded 26,899 calls for service in 2018. RPS fielded around five times as many calls – a number that includes 911 calls for emergencies that didn’t require the police to respond and 1,980 alarm calls, 99.4 per cent of which were false alarms – but received 644 times as much funding from the city.

And Mobile Crisis is the social development group that received the most funding of any in Regina in the 2019 budget. Other non-profits that the city considers “community partners” that combat homelessness, hunger, and poverty, like the food bank and Carmichael Outreach, or that try to fill the gaps left by an under-funded, under-valued mental health care system, like the Regina branch of the Canadian Mental Health Association, received only a fraction of the support Mobile Crisis did. All told, the City of Regina gave $489,535 in funding to the organizations “that will help achieve the City’s priorities related to Social Development” – a meagre offering that shows how low a priority social development is for the city, and that leaves many organizations stretching themselves even thinner as they devote resources to fundraising.

Some groups, like White Pony Lodge in Regina’s North Central, where the effects of poverty cut the deepest, have been relying on GoFundMe campaigns and personal donations to do the kind of community work that often falls to the police, like providing assistance to unhoused or intoxicated people. In 2018, 1,519 of 8,738 individuals in police custody – 17 per cent – were under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol with nowhere else to go, a statistic reflecting the countless gaping holes in the social safety net, from a lack of affordable housing to a shortage of beds in treatment and detox centres. One of the many goals of patrols like White Pony Lodge – which was modelled after Winnipeg’s Bear Clan Patrol – is to intervene in the kinds of situations where intoxicated people might otherwise end up in cells.

Mobile Crisis fielded 26,899 calls for service in 2018. RPS fielded around five times as many calls – a number that includes 911 calls for emergencies that didn’t require the police to respond and 1,980 alarm calls, 99.4 per cent of which were false alarms – but received 644 times as much funding from the city.

White Pony Lodge patrol coordinator and board member Leah O’Malley says that while the group will alert police if there’s serious danger, “we’ve only ever called them a couple of times” since the patrols first started in 2016. Recognizing that the acute problems they face during their patrols – like overdoses, fights, and people with nowhere safe to go – need to be treated at the root, the volunteer-run organization does what it can to help people before they end up in an emergency, hosting open houses where people can get warm in the winter and picking up dangerous items like used needles and knives. But, she says, “it would be nice if we could get some funding.” And unlike the police, “we’re very cheap to run.”

O’Malley agrees that there’s more evidence of meth use in the neighbourhood these days, but she also says that when there are non-law-enforcement investments in the community – like the mâmawéyatitân centre and new parks – it doesn’t take long for there to be noticeable positive impacts on the lives of people who live there. “We see more families out together,” she says. “The neighbourhood is cleaner; people are taking more care around their properties. There’s a community atmosphere. People are becoming more community minded.”

But it isn’t enough. “We need transitional support systems and long-term support systems,” she says. “Jobs training, homes. Just some funded programming. We’re just people.”

Regina’s police chief, Evan Bray, is willing to admit that alternative solutions to policing people with addictions and mental illnesses exist and that they can and should be prioritized. “Investment in social justice issues is something that is extremely important to make a long-term and sustainable difference in not only the health and happiness and wellness in our community, but also in crime and safety as well,” he says, adding that those services need robust funding to be effective. “We need to ensure as a society that those supports, instead of police, are going to be funded and resourced to a point where they can deal with them. Because the absence of instant access to those types of intervention resources and recovery supports would be a recipe for disaster.”

“We live in a wealthy society. We should have free transit and we should have use of community services and we should have well-resourced and supported schools. It shouldn’t be an either/or.”

But Bray, whose police service spent $750,000 on the purchase of an armoured vehicle in 2018 and killed two men in 2019, stops short of conceding that the money should come out of his $92 million budget. “I don’t know what I can cut without being [un]able to deliver a service to the community, or quick response times, or whatever.”

“To me it’s not an either/or. To me it’s that we need to find ways to properly fund the police service to meet the demands and the pressures and the expectations of the community, and at the same time find ways, equally as important, to dig into these social justice issues.” He adds, “Often police involvement is the mechanism to get them involved in some of these social justice streams.” But using the police and the justice system as a mechanism to get individuals the health care they need is not just costly and unreliable – it’s dangerous. Over 70 per cent of the people killed by the police in Canada experience mental illness and addictions.

Shantz says finding ways to fund everything needed to bring compassionate care and social justice solutions to communities isn’t difficult. “We live in a wealthy society. We should have free transit and we should have use of community services and we should have well-resourced and supported schools. It shouldn’t be an either/or.”

Or maybe it should, at least for some things.

“You could also just say ‘we’re going to carve off whatever we need from the police budget and put it into those things instead of policing.”