The colourful history of LSD trials in Saskatchewan

A review of Wonder Drug: LSD in the Land of Living Skies

“Could it be that the most remote frontiers of 21st century exploration lie inside the human mind?”

Author Hugh D.A. Goldring closes his graphic novel with these words, summing up 70 years of psychedelic drug research, and pointing toward its optimistic future.

In Wonder Drug: LSD in the Land of Living Skies, Goldring guides readers on a journey through the history of LSD, and its use both as a recreational drug and a chemical compound with profound medical potential for the treatment of severe mental illness. Goldring’s narrative is accompanied by the vivid illustrations of artist nicole marie burton, his collaborator on two other graphic novels.

Although the novel opens in 1953, it was inspired by the contemporary research of Erika Dyck, Canada Research Chair in the History of Medicine at the University of Saskatchewan. It focuses on the history of LSD trials in Saskatchewan, where, in the 1950s and 1960s, researchers conducted human trials on themselves and patients at the province’s Weyburn Mental Hospital. Goldring follows LSD researchers as they made groundbreaking discoveries that were ultimately met with backlash from the public and pharmaceutical companies, misinformation that led to a moral panic, and a war on drugs that sidelined LSD’s potential as a treatment for mental illness.

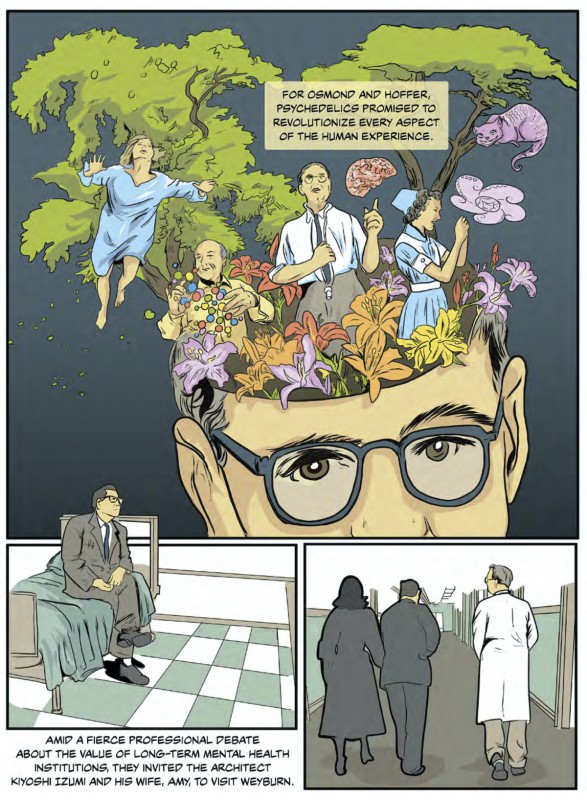

The interest in LSD in the early 1950s came from two main sources. The first was those who saw it as a way to fuel their spiritual journeys, like the writer Aldous Huxley whose story opens the book. The second was scientists, particularly Humphry Osmond, who was introduced to LSD by Huxley; Osmond saw the drug as a gateway into the minds of patients who were experiencing psychosis and saw its potential as a cure at most, a comfort at least. Goldring notes that the term “psychedelic,” which translates to “mind made manifest,” arose out of correspondence between Huxley and Osmond.

Goldring follows LSD researchers as they made groundbreaking discoveries that were ultimately met with backlash from the public and pharmaceutical companies, misinformation that led to a moral panic, and a war on drugs that sidelined LSD’s potential as a treatment for mental illness.

burton’s realist style of illustration is well-suited to the subject, and the muted colour palette – yellows, browns, and greens – is reminiscent of the era. With clean lines and a pastel – and occasionally greyscale – palette, she conveys both the ordinariness and the extraordinariness of what was happening with LSD research. The realistic style emphasizes the scenes where characters use psychedelics. burton’s illustrations become more vibrant and surreal as the book continues, and the experience of drug use is conveyed through clean lines of vibrant light, ribbons of colour, and explosions of lush, riotous flowers – as well as scenes of near terror, when scaly hands reach for users while the faces of children morph into the heads of hogs.

The graphic novel covers decades of research and this barrage of information sometimes becomes confusing. Goldring jumps quickly from character to character, not always emphasizing the importance of each person to the narrative and to the research. Some characters are introduced early, but just as quickly fall out of the story, such as John Smythies, who is introduced as Osmond’s collaborator but is never mentioned again. And burton’s artistic style is limited when it comes to creating strong identifying characteristics for individual characters. Instead, the reader must rely on contextual cues from the text to know who is speaking.

At one point we’re introduced to Kiyoshi Izumi, an architect who was invited to Weyburn to help scientists understand the role that building design played in the mental health of institutionalized patients. Before visiting the Weyburn Mental Hospital, Izumi took LSD to mimic the perceptions of people with psychosis, and found that the mental hospital was a horrifying place: “the corridors seemed infinitely long … echoes sounded like voices … dark colours appeared as holes in the surfaces.”

He proposed a new LSD-inspired design to make hospitals more inviting and comfortable for mentally ill people. However, his project was cancelled by Ross Thatcher’s Liberal government, which had recently replaced the social-democratic Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) government.

But Goldring does not fully convey the details of Izumi’s ideas, nor why they were dismissed. He does, however, go on to explain Izumi’s understanding of environment in relation to mental health and LSD trips and how this understanding relates to Al Hubbard’s theory of set and setting, which holds that good environments and positive stimuli foster better trips. But it is unclear whether Izumi’s and Hubbard’s theories arose separately or together.

These points then tie into the main thread that runs through the graphic novel: Osmond’s hope that LSD can cure or treat mental illness, and perhaps many other diseases. Goldring’s political stance also becomes more evident here, as the first half of the novel occurs while the CCF is in power with Tommy Douglas at its helm, during which time LSD is seen positively. Once the Liberals come into power, though, we see LSD’s reputation sour as it becomes a threat to societal norms.

LSD gains most of its negative reputation due to the war on drugs – this is another instance where Goldring’s barrage of research becomes overwhelming on the first read. Goldring alludes to the public’s disapproval of LSD at various points throughout the novel, even before the political transition from the CCF to the Liberals. Early on, he mentions how Osmond and his research partner, Abram Hoffer, partnered with the local chapter of Alcoholics Anonymous. The drug’s success in treating alcohol addiction attracted the organization’s co-founder, Bill W. – but as a founder of an organization dedicated to sobriety, he was concerned that it would damage his credibility. Despite his decision to quit using the drug, he continued to quietly support Osmond and Hoffer’s work. This scene doesn’t feel very important when mentioned this early in the graphic novel, but when paired with the later scenes that detail the war on drugs, it shows how LSD seemed to straddle the line between good and bad even during its early days.

Goldring has us consider LSD’s public image in comparison to similar drugs, namely peyote (a cactus that produces mescaline, another psychedelic). He explains how, while LSD research was being authorized and supported by the government, members of the Native American Church were being prosecuted for their traditional use of peyote in religious rituals, with the government denying members the ability to import peyote into Canada. These days, the Native American Church has legal access to the substance, but the stigma remains. The scene’s position in the story feels random, but the information that follows helps to clearly tell the story of drug criminalization.

Press coverage described the drug as “a monster that shrank the brain and damaged your DNA” despite all scientific evidence showing that deaths from LSD were on par with those from other pharmaceuticals and, in fact, LSD had no known fatal dosage.

Similar to how peyote challenged the religious status quo, LSD challenged the cultural and political status quo. As LSD became more widely available and grew in popularity as a recreational drug, Goldring explains how it attracted “spiritual seekers, Bohemian artists, and political radicals,” primarily the hippies of the 1960s countercultural movement. Press coverage described the drug as “a monster that shrank the brain and damaged your DNA” despite all scientific evidence showing that deaths from LSD were on par with those from other pharmaceuticals and, in fact, LSD had no known fatal dosage. Very quickly, LSD went from a miraculous wonder drug to a lethal substance. Unfortunately, this fearmongering and misinformation is all too familiar to us today, as we wade through misguided arguments against COVID-19 vaccines.

Eventually the negative stigma surrounding LSD extended to all recreational drugs, partly in an effort by the United States to discreetly target Black communities. Goldring quotes a statement made by President Richard Nixon’s chief domestic advisor, John Ehrlichman, who admitted, “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black … but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and the blacks with heroin … and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities.” LSD and other recreational drugs did not become “bad” drugs based on their actual properties, but because of who was using them.

Goldring moves through each of these points very quickly. As individual events, they’re missing lots of context, but as part of the larger narrative, each one helps describe the graphic novel’s main takeaway: that there is a constructed divide between “good” and “bad” drugs. Good drugs, Goldring says, are given by doctors, and bad drugs are associated with eroding the moral fabric of society. This divide persists today, and severely impacts the lives of many drug users who are denied help and punished. Addiction is seen as a moral failing and a personal choice, rather than a condition that requires medical care.

Goldring sees a hopeful change to this stigma, though, as some institutions in Canada have received permission to administer psilocybin, known colloquially as magic mushrooms, as a treatment for depression and for end-of-life acceptance for patients in palliative care.

Wonder Drug offers a unique and inspiring look into the history of LSD and recreational drug use in Canada, and specifically Saskatchewan, over the last 70 years. Works like this one are integral to challenging the stigma around drugs as we move toward decriminalizing their use, funding safe consumption sites, and even combatting racism.