The great Saskatchewan tuition crisis

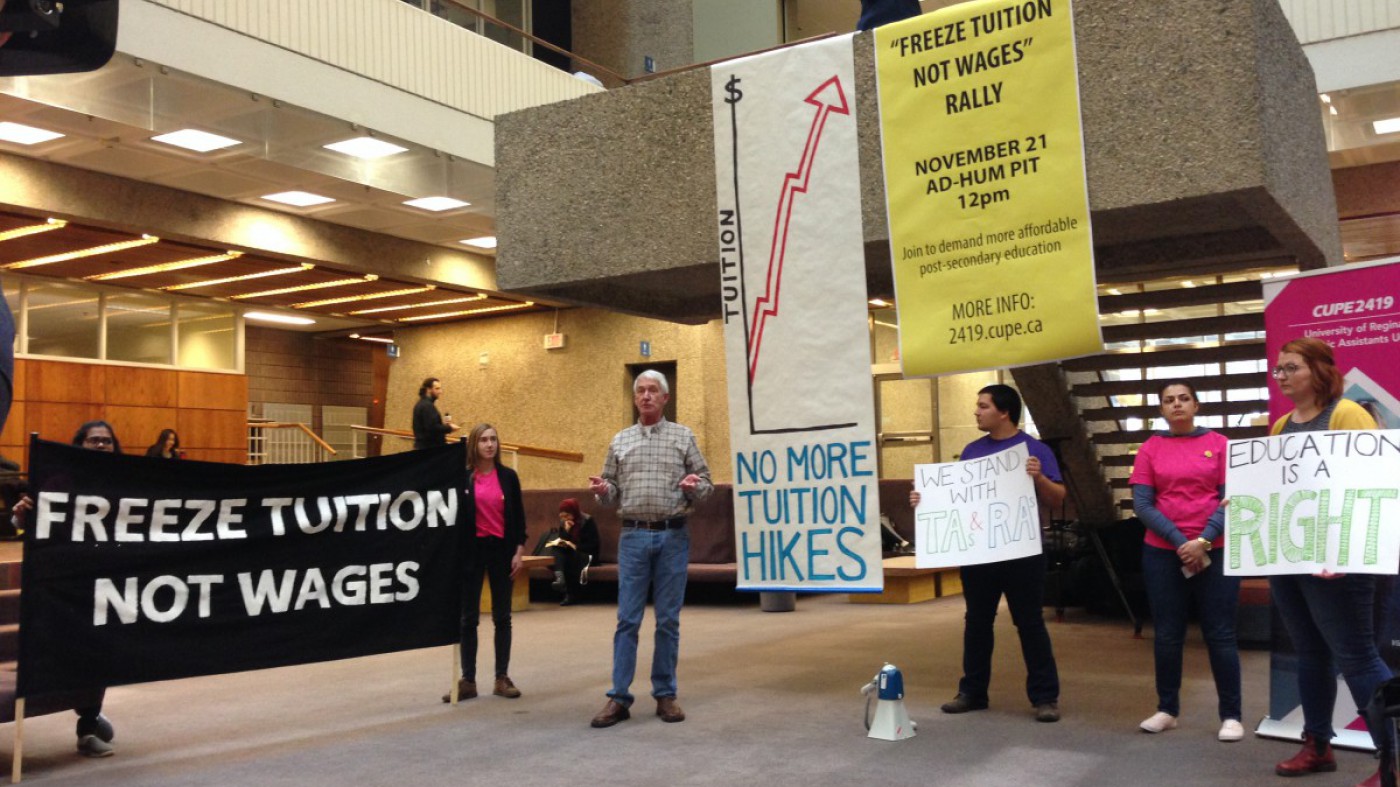

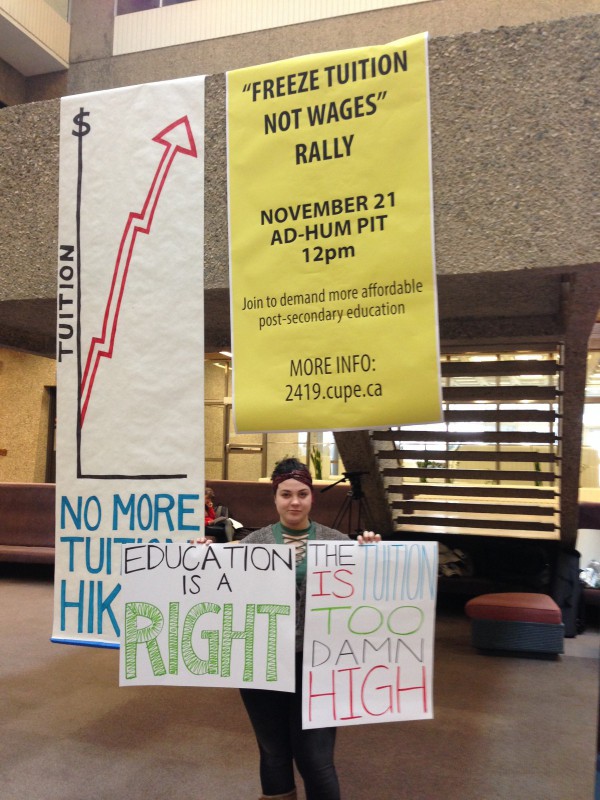

A rally calling on the University of Regina to freeze tuition in November 2018. Photos by Eagleclaw Bunnie

Everyone from debt specialists to the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS) to private-sector unions agrees: Canadian students and post-secondary grads are facing a debt crisis. Between 1999 and 2012 – already nearly a decade ago, the last time CFS analyzed student debt levels in depth – the debt students owed to various levels of government increased by 140 per cent, and lines of credit – including student lines of credit – have increased more than 436 per cent, numbers that beggar the imagination. Today, Canadians owe $28 billion in student debt – an amount that is the equivalent of 1.7 per cent of the country’s GDP and doesn’t include other forms of debt that students incur, like lines of credit and credit cards.

Around $75 million of that government debt can be claimed by former Saskatchewan students. In Saskatchewan, undergraduates owe more on average than other Canadians at time of graduation and are more likely than other Canadians to leave school with “large debt” (amounts over $25,000). Saskatchewan grads are, however, less likely to leave school with debt in the first place. Tuition at the two largest post-secondary institutions – the University of Regina and the University of Saskatchewan – increased every year for the 11 years between 2008 and 2019, although both institutions “froze” tuition in 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Saskatchewan domestic students still pay significantly higher tuition than the national average and the third highest tuition in the nation. It’s a social crisis that has arisen from more than a decade of shifting the costs of operating ostensibly public institutions away from the government and onto the shoulders of students.

What is very clear, though, is that tuition rates have increased by staggering amounts, far outstripping increases that could potentially be blamed on inflation.

By 2009, around one-quarter of university revenues in Saskatchewan came out of the pockets of students, a 10 per cent jump since the 1990s, when tuition fees were about one-fifth of what they are now. The increase in tuition has been accompanied by a shift in how much support higher education receives from the province. In 1974, 92 per cent of revenues in Canadian university operating budgets came from government funding. By 2012, that figure was only 55 percent. So while it’s true that the amount of funding that the government provides for post-secondary education has risen over time, the proportions of support have shrunk dramatically. Compare this with K-12 education, which is also public, and which receives 100 per cent of its funding from provincial revenues and local property taxes. There’s little in the way of plausible explanations for why public universities are funded in such a radically different way.

What is very clear, though, is that tuition rates have increased by staggering amounts, far outstripping increases that could potentially be blamed on inflation. Between 2000 and 2020, tuition for domestic undergraduates at the U of S has increased by roughly $2,400. For the average student in Saskatchewan, a four-year degree will end up costing them between $26,000 and $30,000 in tuition fees alone.

According to the CFS, the massive debt load incurred in these programs “appears to be driving committed young doctors away from family practice and young lawyers away from the public service and pro bono work.”

Tuition for certain professional programs has also increased exponentially during this same period. Between 2000 and 2019, the annual law school tuition in Saskatchewan has more than tripled, from $3,516 in 2000 to $14,064 per year in 2019. One year in the faculty of medicine has increased by more than $12,000, from $5,815 to $17,998. The Canadian Federation of Students notes that massive tuition increases in professional programs like medicine and law have a negative impact on society at large. According to the CFS, the massive debt load incurred in these programs “appears to be driving committed young doctors away from family practice and young lawyers away from the public service and pro bono work.”

The burden of student debt – and the interest it accrues – is a dangling sword that warns educated professionals away from pursuing careers that would be for the public good but don’t pay as well as private-sector jobs and more profitable specialties. This has very real consequences, as people who might have otherwise dedicated themselves to environmental protection, community health initiatives, or fighting the inequities of the justice system are forced to dedicate themselves to servicing their debt instead.

In some cases, the threat of spending roughly a decade of one’s early adulthood paying off student loans has led to many high-school graduates – particularly those who are marginalized because of race and disadvantaged economically – bypassing post-secondary education altogether. It’s a decision that makes an unfortunate amount of sense: students who have to borrow from the government will end up paying, on average, an additional $5,000 to $10,000 over the course of the 10 years it usually takes someone to pay off their loan. And those who require repayment assistance – either the temporary or permanent extension of their repayment period, or up to a year of interest-only payments – will ultimately pay even more in interest. It’s a Kafka-esque system that exacerbates the inequalities between those who can afford to pay for their education outright and those who cannot. It’s a cruel irony that education – traditionally a path out of poverty – costs the poor more.

The burden of debt

When pressed on tuition and post-secondary funding-related questions, politicians and university administrators will often point to grants and scholarships as ways that students can reduce their debt burden. While grants and bursaries are beneficial to some students, they’re not real solutions, and framing them as though they are blithely ignores that the financial need for which the grants are supposed to compensate has been manufactured by the government and administration themselves. Applying for financial assistance can also be taxing. “I found it challenging,” says Dayton Buchanan, a third-year student majoring in economics and business administration at the University of Regina, of the steps involved in applying for scholarships and grants. It’s frequently a multi-part process that requires financial disclosures as well as references and personal essays. When you factor in the time spent navigating complex systems of funding together with time spent working outside of school, students who can’t afford to pay for their education out of pocket don’t just end up paying more money for their education, they also spend more of their time. And just like the degree itself, doing the work of applying for grants and scholarships is no guarantee that you’ll get a return on that investment.

“I don’t think we could have survived if I hadn’t been working. I remember thinking, ‘how did we afford to live?’”

In order to keep their debt burden as low as possible – or simply to keep food on the table while they attend school – more than half of students work throughout their degree to make ends meet. For some, the time they spend on their job compromises the quality of their education. “If I didn’t have to work during the semester and could solely focus on school, that would be reflected in my marks,” says Buchanan. He’s not alone. One-third of students report that employment has had a negative effect on their education. But for many, it’s simply not a choice. “I don’t think we could have survived if I hadn’t been working,” says Lori Morphy, a graduate of the University of Saskatchewan and the University of Alberta who worked multiple jobs throughout the entirety of her bachelor’s and master’s programs. “I remember thinking, ‘how did we afford to live?’”

Most student loans go into repayment after six months of someone finishing their classes. That means graduates have less than a year to find stable employment and secure housing before they must start servicing their debt. For many, it’s simply not possible. Of the 5,041 Saskatchewan borrowers whose loans went into repayment in 2017, 20 per cent needed repayment assistance immediately. That’s 1,008 graduates who convocated with a debt load that was already unmanageable. While student debt is uniquely difficult to discharge, the federal government frequently ends up writing off hundreds of millions of dollars in student loans, something that should – but somehow doesn’t – trigger a reckoning for the policymakers behind higher education.

"I came out of school $30,000 in debt [10 years ago]. What are my kids going to experience when they come out of school?”

And even for those who can afford to make their monthly payments, paying off the principal and interest on loans means deferring their future. Morphy, who graduated with a master’s degree in 2010 and is set to make her final student loan payment this year, says that she and her husband have had to put off saving for retirement while she pays off her loan. And she’s worried about what rising tuition means for the present and future of her own children. “I feel like it’s getting more and more inaccessible to people,” she says. “It’s getting harder and harder to live day to day and still pay tuition. […] I came out of school $30,000 in debt [10 years ago],” she says. “What are my kids going to experience when they come out of school?”

Where is Saskatchewan’s student movement?

While the landscape is grim, there’s no reason it needs to stay that way. University revenues in all areas have risen over the past decade, so the issue isn’t a lack of resources, but rather how those resources have been allocated. A report from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives says that the money from research grants, government funding, and tuition have “benefited administrations and non-academic programs,” but, they say, “students and faculty members have not benefited proportionately.” Cuts to administrative salaries and reductions in the number of high-level administrators would go a long way toward redistributing revenues to those whom universities cannot run without: students, faculty, and support staff.

What is lacking then, is the political will. Though it’s difficult to see the possibilities when in the midst of a crisis, Saskatchewan students should look to Quebec for guidance on how to build the kind of militant student movement that can win real concessions from administrations and governments. In 2012, students in Quebec, together with labour unions and community groups, staged massive protests in the streets of Montreal, the culmination of years of work. They ultimately stopped a planned tuition hike and even unseated Jean Charest’s governing Liberals. In the years since, the student movement has repurposed itself as an anti-austerity, anti-extractivist movement, demonstrating the ways in which unified movements are able to mobilize members against any number of issues.

Cuts to administrative salaries and reductions in the number of high-level administrators would go a long way toward redistributing revenues to those whom universities cannot run without: students, faculty, and support staff.

But that kind of combative student unionism isn’t present in Saskatchewan right now, although Kent Peterson, the former president of the University of Regina Students’ Union, says that that can change. “If engaged with properly, student unions hold a lot of power,” says Peterson. “They have the entire power of the student body. Those are many thousands of taxpaying, working, voting citizens in one place,” he says. “They can have a lot of sway over decision-makers.” In May, Peterson’s 13-year fight to get the University of Regina to sell the home where university presidents have lived rent-free on the students’ dime ended in victory.

Peterson, who now serves as secretary-treasurer for the Saskatchewan branch of the Canadian Union of Public Employees, says it’s “critical” for student unions to engage with labour unions and vice versa. “The folks that are keeping the campus clean and keeping the boilers running and teaching classes […] provide the learning environments that students need to work in,” he says – but it’s a two-way street. “None of those folks would have jobs without the students there,” he explains. “So, don’t you think the issues they face are the same in terms of proper funding, proper accountability and transparency measures, and the management of the administration? At a very core level, the issues they face are the same.”

Peterson says there has never been a better moment to create the kind of unified student movement necessary to win profound changes in the way universities work. “Public opinion polls consistently show that folks of all ages consistently support freezing, lowering, or eliminating tuition. So that support is there,” he notes.

“We need to start talking about not just reducing tuition, but eliminating it altogether in a real way.”