The present and future of Saskatchewan’s emissions and energy

Nuno Marques/Unsplash

By mid-July 2021, Saskatchewan’s wildfire count had already exceeded the five-year average by more than 200 fires. For long stretches of time much of the province was under heat and air quality warnings as smoke from the fires, almost all of which were north of Prince Albert, drifted into the south, blanketing the province in smog. The intense heat and accompanying drought, along with the smoke from the fires, was a potent reminder that the climate crisis has already arrived in Saskatchewan.

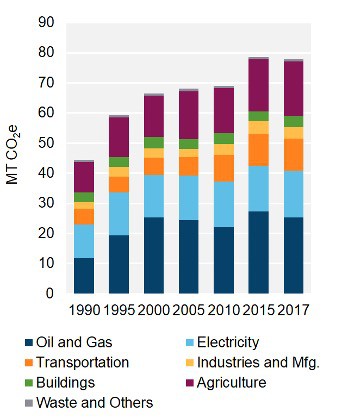

"This stacked column graph shows GHG emissions in Saskatchewan by sector every five years from 1990 to 2017 in MT of CO2e. Total GHG emissions have increased in Saskatchewan from 44.4 MT of CO2e in 1990 to 77.9 MT of CO2e in 2017." Graph via the Canada Energy Regulator website, with data from Environment and Climate Change Canada's National Inventory Report.

But despite the catastrophic impact climate that change is having on Saskatchewan communities and ecosystems, the province remains the single highest per capita emitter of greenhouse gases (GHG) in Canada. While only having 3 per cent of the country’s population, Saskatchewan accounts for almost 11 per cent of Canada’s total GHG emissions. The Sask Party government has been reluctant to do anything meaningful to reduce emissions, actively sabotaging the province’s solar industry and devoting untold resources to fighting the carbon tax. The official opposition, the Saskatchewan NDP, also supports pipelines and has yet to present a bold vision for a decarbonized Saskatchewan.

The situation is dire, but there are pathways to a just transition away from fossil fuels. In search of these hopeful solutions, I spoke to experts about the present and future of Saskatchewan’s emissions and energy. While the solutions suggested here are by no means comprehensive, they’re meant to encourage readers to think about some of the unique problems that are facing the province, and to provide insight into ways forward.

Setting targets

Brett Dolter is an assistant professor of economics at the University of Regina who researches climate change and energy policy. Dolter says that the province is at the point where it needs to be decarbonizing all sectors at once.

“At the same time that we are working towards a zero-emissions electricity system in Saskatchewan, we need to be working to electrify vehicles and buildings, and working with industry to find zero-emissions production processes,” he explains.

He adds that there are a few technical barriers to decarbonization – other experts, for example, have pointed out that renewable energy has a lower energy return on investment, meaning that we need to use more energy to extract or produce energy from renewable resources. But the most significant barriers are political and ideological – and opposition to renewable energy is often rooted in misinformation.

Dolter says that Saskatchewan is well behind other provinces when it comes to addressing climate change. “As Efficiency Canada found, we lag behind every other province on [energy efficiency] policy and programs,” he notes. “The Pembina Institute came to a similar conclusion, finding that Saskatchewan lacks the basic elements of a successful decarbonization strategy like emission reduction targets.”

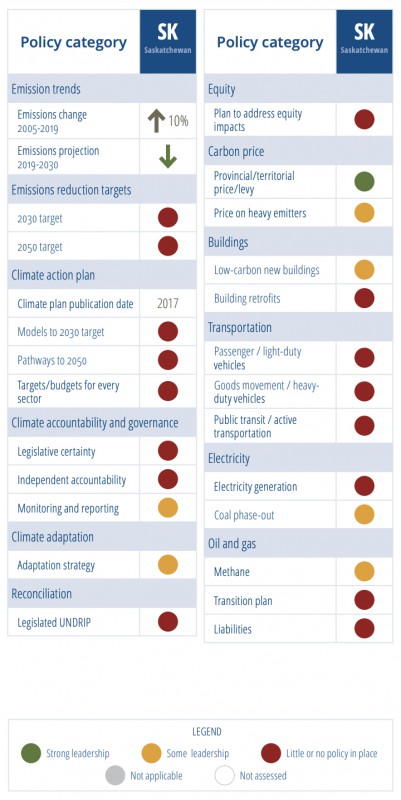

The Pembina Institute's assessment of the the state of climate action in Saskatchewan. Dusyk, Nichole, Isabelle Turcotte, Thomas Gunton, Josha MacNab, Sarah McBain, Noe Penney, Julianne Pickrell-Barr, Myfannwy Pope. All Hands on Deck: An assessment of provincial, territorial and federal readiness to deliver a safe climate. The Pembina Institute, July 2021.

The Pembina Institute gave Saskatchewan poor-to-middling scores on nearly every policy category related to climate change, noting that the province has few to no policies in place for an oil and gas transition plan, or for climate action targets and budgets for various sectors. The closest thing Saskatchewan has to a robust greenhouse gas emission reduction target is its commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in electricity production to 50 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030, and net zero by 2050. But overall, the Government of Saskatchewan’s climate change strategy, “Prairie Resilience,” is essentially a plan to weather the storm of cataclysmic climate change, rather than mitigate it – although the Pembina Institute notes that the government’s climate change adaptation plan is lacking, too.

Given the scale of the problem, it’s not surprising that Dolter argues that the solutions need to come from across society, not just from elected officials. “All citizens, employees, business and labour leaders, First Nations, and elected officials [need] to work on the shared mission of achieving a zero emissions future in Saskatchewan,” Dolter says.

Agriculture

The National Farmers Union (NFU) released a discussion paper in late 2019, Tackling the Farm Crisis and the Climate Crisis: A Transformative Strategy for Canadian Farms and Food Systems.11 In their report, lead author Darrin Qualman and the NFU present the twin crises farmers face, which they argue have the same sources and solutions. The paper begins bluntly: “6.4 degrees Celsius. That’s the amount of warming that may ravage many areas of Canada this century. Unless we do something. This report outlines how farm families can contribute to doing something.”

As previously noted, agriculture accounts for almost a quarter of Saskatchewan’s emissions. Canada-wide, about 29 per cent of agricultural emissions come from the soil, mainly due to the use of nitrogen fertilizers – both as it is manufactured and when it is turned into nitrous oxide by microbes in the soil. Another 30 per cent comes from livestock (mainly cattle), and 11 per cent comes from the production and combustion of fuel. Interestingly, livestock and fuel emissions have plateaued since reporting started in the ’90s; today, increases in emissions are coming from nitrogen fertilizers.

Considering these facts, the NFU outlines a plan to reduce agriculture-related emissions by 30 per cent by 2030 and 50 per cent by 2050, all while keeping profits local.

Qualman and NFU’s report features many general and specific recommendations to lower emissions. The authors call for both using more data, science, and technology in agriculture, in addition to returning to practices and norms from before the domination of agribusiness corporations, when farming shifted from being a solar-powered, low-input, net-zero emissions subsistence project to being propelled by fossil fuels and nitrogen fertilizers, which allows for increased production but has catastrophic impacts on the climate and ecosystems.

“The task before us is to rewire, replumb, re-fuel, and re-tool Saskatchewan. That will take a lot of work. Transforming our energy and civilizational systems will create and sustain huge numbers of new jobs. The idea that tackling climate change would be a job killer is among the least-informed opinions ever.”

On top of proposing a return to environmentally sustainable agriculture, Qualman and the NFU point out that at least part of the problem is linked to the “farm income crisis.” Agribusiness corporations have monopolized the industry and put family farms all across the province in debt they can’t escape from. The challenge posed by agribusiness is compounded by the challenges of the climate crisis, which is leading to increasingly unpredictable weather, including prolonged and catastrophic drought. A 2020 report from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, also co-authored by Qualman, found that in a single generation, the number of young farmers has been reduced by 70 per cent, which the CCPA argues is a result of an approach to agriculture “too focused on maximizing production, exports, input use, energy use, farm size, and technology dependence.”

Agriculture that is sustainable – both environmentally and economically – requires embracing regenerative agriculture, moving to minimum-input no-till (MINT) farming, restoring methods of managing prices and production like the Canadian Wheat Board, putting aside land for ecological reserves, and restoring wetlands and shelterbelts (plantings used to protect the land from wind and erosion).

I asked Qualman if he had any information on how this program would impact jobs, and he told me he didn’t have anything specific but did add: “The task before us is to rewire, replumb, re-fuel, and re-tool Saskatchewan. That will take a lot of work. Transforming our energy and civilizational systems will create and sustain huge numbers of new jobs. The idea that tackling climate change would be a job killer is among the least-informed opinions ever.”

Qualman calls for more than just agricultural reforms. He’s pushing the Saskatchewan NDP to “embrace the idea of a Saskatchewan Economy 2.0 – a new vision of collective prosperity and mutual support; renewable energy and retrofits; low-emission sustainable food production; and inclusion, equity, opportunity, and peace of mind for all citizens.”

Decarbonize electricity

If we look at electricity use in Saskatchewan, a few interesting things are going on. For starters, it’s dirty. Forty per cent of our electricity comes from coal and 43 per cent from natural gas. Now, if we look at electricity demand, only 22 per cent is used residentially or commercially. Fifty-nine per cent goes to industry – especially big power accounts like uranium and potash mines and the oil fields. In fact, speaking at a 2018 conference on a just transition for Saskatchewan, Drs. Emily Eaton and Simon Enoch confirmed this, saying, “just 35 customers use 45 per cent of the electrical power in the province.”

This tells us two things: first, we need to get off coal and natural gas and bring in renewables; second, corporations are responsible for most of our emissions, not individuals.

The federal government plans to phase out coal all across Canada by 2030. In the meantime our provincial government is equipping plants with carbon capture and storage technology.

Instead of looking for ways for individuals to use less electricity in their homes (which is a good thing to do but is not a comprehensive climate strategy), we should be demanding the multi-billion dollar corporations lower their electricity demand.

Even after we get off coal, we still have to transition off of natural gas. This particular point is where the Sask NDP and many other progressive groups in Canada fall short. Natural gas is often talked about as a necessary transition fuel between coal and renewables. This may have been true 20 years ago, but we don’t have time. Canada has already warmed 1.7 degrees above pre-industrial levels and we only have nine years left to limit climate change below a global average temperature rise of 1.5 degrees.

Transitioning off fossil fuels to renewables with the decade may seem daunting, but I return to my second point: corporations are responsible for our emissions, not individuals.

So instead of looking for ways for individuals to use less electricity in their homes (which is a good thing to do but is not a comprehensive climate strategy), we should be demanding the multi-billion dollar corporations like Nutrien, Cameco, K+S Potash Canada, and Husky Energy lower their electricity demand. In the case of the uranium mines and oil fields, we should just completely shut them down and re-employ the workers to clean up those same projects.

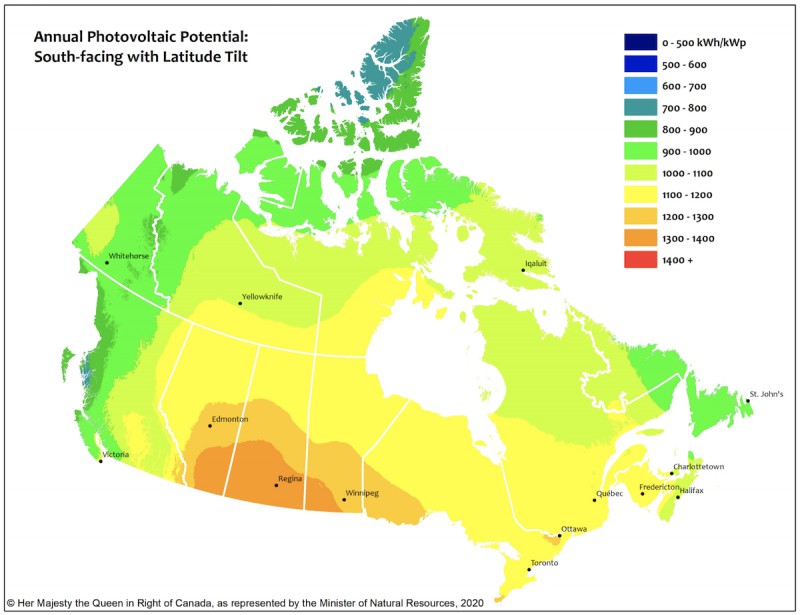

Fortunately, Saskatchewan has plenty of alternatives to coal and natural gas. Saskatchewan has the some of the highest wind and solar energy potential in Canada – according to Natural Resources Canada, the coal community of Estevan even rivals cities like Los Angeles and Mexico City in terms of solar potential. There are some legitimate concerns about the intermittency of renewable energies like wind and solar. However, having both with strong potential will help deal with intermittency problems – in other words, it’s usually either sunny or windy in Saskatchewan.

Photovoltaic potential of regions of Canada. Map via Natural Resources Canada.

To learn more about decarbonizing electricity in Saskatchewan, I interviewed Rylan Urban, the founder of EnergyHub.org, which publishes annual solar power guides and rankings for Canada’s provinces. Urban assures me that Saskatchewan has a high enough solar potential to power our province: “[solar] panels on every roof and a solar farm near every city would probably do the trick. It's a lot, but it's not a cover-all-the-farmland-in-the-whole-province kind of thing.”

I am hesitant to advocate for covering the province in solar cells, because of the environmental and human impacts of lithium mining. Lithium-ion batteries are used for solar energy storage, and the process of mining lithium uses massive amounts of water as well as chemicals that can leach into the surrounding environment with devastating impacts on ecosystems. Plus, like many mining operations, lithium mines in poorer countries like Chile are often owned by capitalists in wealthy countries like Canada, meaning that profits from natural resources end up leaving the impoverished communities where they’re found. Plus there are technical barriers to reshaping our electric grid to be entirely reliant on solar power. Fortunately, there are other options to decarbonize electricity in Saskatchewan.

Super-grids are an excellent way to ensure reliable energy supply, especially when some renewable energies are dependent on intermittent weather patterns. Canadian researchers have begun suggesting building a super-grid for the Prairies connecting Saskatchewan, Alberta, and Manitoba to enable transmission of clean energy between provinces whenever one province encounters issues meeting demand. Dolter recently wrote about why Canada should invest in super-grids, arguing that interprovincial transmission lines between the western provinces could allow for wind and solar farms in Saskatchewan and Alberta to build resilience to weather variation by using hydroelectricity in British Columbia and Manitoba as backup power sources.

Some interprovincial transmission links exist; this would be a matter of scaling them up. A 2019 report by Manitoba Hydro and SaskPower explored increasing interprovincial transmission by the year 2030. The most promising option they reported was building two ac transmission lines (alternating current, meaning an electrical current could flow in either direction) connecting Winnipeg and Regina. The authors discuss the potential for other transmission lines as well, and estimate they could achieve a 1,000 MW transfer increase with a $1.8 billion investment.

When reached for comment, Dolter says that a larger interprovincial project “has merit” and is “definitely an idea worth exploring.” He also mentions that most of the research has been conceptual and that more detailed modelling is needed.

Electrify everything!

This is where things will get tricky, and we’re going to have to use our imaginations a bit.

In addition to building up a clean electrical grid, we need to move transportation and space heating to electricity. This is still a lot of electrical demand to handle and build up, so we should also improve efficiency in transportation and buildings in order to lower demand.

Deep energy retrofits – making changes to improve the energy efficiency of already-existing buildings – are a personal favourite of mine because they’re like a quintuple threat of good times: create local jobs, improve the health of occupants, lower the carbon footprint, lower energy poverty, and increase climate resilience.

The Government of Canada plans to ban the sale of gas-powered cars by 2035 and transition people to electric vehicles. This presents an electricity demand problem for future electrical grids, especially if we’re also electrifying space heating and cooling. That’s why we need to think beyond electric cars and back to buses. In his book Do Androids Dream of Electric Cars, James Wilt discusses the problems with the status-quo transit culture and explains very non-radical, easy solutions. To quote his book:

“The irony is that many improvements to public transportation can be both simple and affordable. Dedicated bus lanes with traffic signal priority can have immediate impacts on reliability and efficiency of transit – and require only a few buckets of paint and new traffic light hardware. Other changes, like all-door boarding and off-board fare payment can reduce the amount of time it takes riders to get on a vehicle.”

“Public transportation works. It's immediately deployable. Entire communities can be overhauled in a few short years to reorient around free transportation. Municipalities can slash greenhouse gas emissions, reduce congestion, convert previously busy streets into wider sidewalks and cycle tracks, decrease fatalities, greatly improve accessibility for seniors and people with disabilities, and reduce assault and harassment of women, trans, and gender-nonconforming people in public spaces.”

Individual efforts will not be enough to lower emissions. Eaton and Enoch echoed this point at the 2018 Just Transition Summit: “If every individual in Saskatchewan reduced their emissions to zero – from their cars, their homes, their electricity consumption – it would only amount to a total reduction of between 10-12 MT of GHG emissions.” It’s a mere dent in the 76.4 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions the province produced in 2018. However, if Saskatchewan is to decarbonize, it is your responsibility as a resident of this province to help us get there. You need to reject politicians that advocate for fossil fuels – green, orange, red, or blue. You need to say no to mines and oil and gas fields. You need to organize your co-workers, your family, your friends, and your church. You need to take power back for a just transition. No one is going to save you, except you working together with others.