Northern forests on the chopping block

Courtesy of John Murray

The pace of logging in Northern Saskatchewan has picked up substantially in recent years and some residents, like those in the new group Protect Our Forest, are raising concerns.

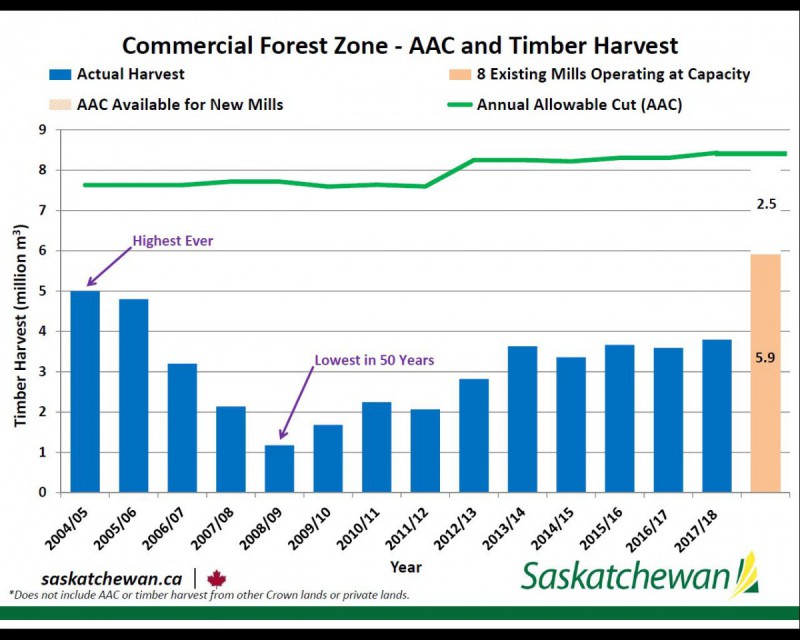

Timber harvesting peaked in 2004–2005 under the NDP government at about five million cubic metres harvested, before a rapid decline in subsequent years. A year after the Sask Party came to power, in 2008–2009, harvesting had declined to a 50-year low of just over one million cubic metres. Since then, the harvest has crept back up to nearly four million cubic metres in 2017–2018, the most recent year with available data.

Saskatchewan Forest Sector Overview presentation, dated March 2019. From Forestry Development branch of the Ministry of Energy and Resources. Link: https://publications.saskatchewan.ca/api/v1/products/80470/formats/92309/download

John Murray, an organizer with Protect Our Forest who lives in Saskatoon, has noticed the large clear-cut tracts around Nesslin Lake and Big River. “We thought Weyerhaeuser was gone and that was it,” Murray tells the Sask Dispatch in an interview. Weyerhaeuser is a logging and forestry company that held a near monopoly on the industry in the province in the 1990s.

“They’d taken so many trees. We thought the forest was going to renew,” Murray continues. “But this new government that we’ve got – I became aware of it in 2016 – have gone back into all those leases that Weyerhaeuser had and they’re cutting anything that’s left,” Murray says.

“I think the provincial government has declared war on the forest,” says Murray. “They’re trying to get every stick.”

And clear-cutting could ramp up. According to available presentation slides from the Forestry Development branch of the Ministry of Energy and Resources, the province’s annual allowable cut is over double what it was in 2017–18. In other words, while the rate of cutting forests has almost quadrupled from 2008–09 to 2017–18, the government has made room for it to double on top of that. According to ministry documents, forest product sales were over $1.2 billion in 2018, and “[f]ull sector development utilizing majority of [annual allowable cut] has the potential to generate over $2 billion in forest products sales annually.”

“I think the provincial government has declared war on the forest,” says Murray. “They’re trying to get every stick.”

According to the government, around 60 per cent of the tree species being logged are softwood – including jack pine, white spruce, and black spruce. Of the hardwood trees being logged, the majority are trembling aspen. Three-quarters of primary forest products are sold out of country – lumber and panels exported to the United States, and pulp exported to China and Indonesia.

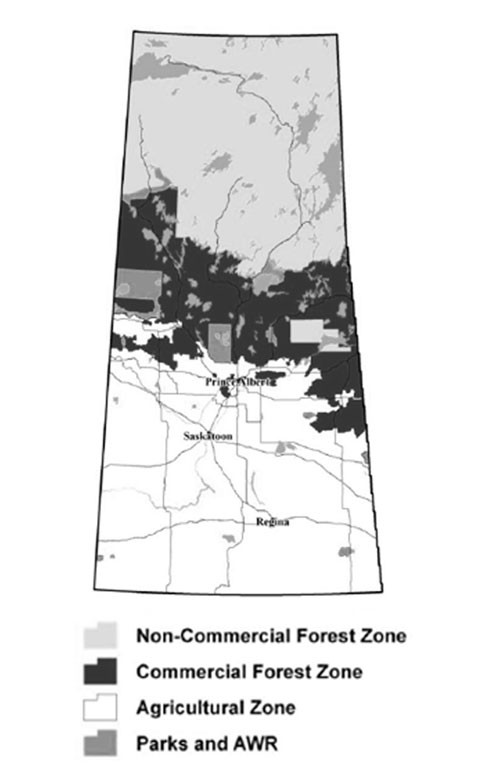

Over half of Saskatchewan – 34.3 million hectares – is forested. 11.7 million hectares is commercial forest zone. Source: Saskatchewan Forest Sector Overview presentation, March 2019. From Forestry Development branch of the Ministry of Energy and Resources.

The region where harvesting is taking place is the southern portion of the boreal forest – or the commercial forest zone, as government documents refer to it – with its southern point at Prince Albert and La Loche as the northern limit. It is primarily in Treaty 6 and Treaty 10 territory, as well as smaller sections of Treaty 8 and Treaty 5 territory.

Thirteen First Nations recently signed the Saskatchewan First Nations Forestry Alliance, a deal negotiated independently of the province. According to paNOW, “[the] deal outlines how business-related opportunities will be handled on First Nations’ ancestral lands, which cover much of Saskatchewan’s forested area. Together, the groups direct forest management licenses and commercial arrangements on more than four million cubic metres of the annual allowable cut in the province.”

Over 30 per cent of the workforce in the industry is First Nations or Métis, the highest in any province, according to the government.

But Murray says some Indigenous residents in northern forests oppose the clear-cutting. “It’s creating conflict – like on reserves, say, that I go to, because some of the Elders especially realize that this practice is really bad,” he explains on Saskatoon community radio show Making the Links. “But other people on the reserve get bought off with money and support the process, and then the companies get to say they have Indigenous participation, but it’s more complex than just that.”

In other words, while the rate of cutting forests has almost quadrupled from 2008–09 to 2017–18, the government has made room for it to double on top of that.

Joys Dancer, a member of Protect Our Forest, lives in Birch Lake near a mill at the edge of the forest and is concerned to see the constant stream of loaded logging trucks. Asked how she’d like to see Saskatchewan’s forestry practices change, she tells the Dispatch “that the management of activities in the forest needs to be in the hands of local people, as well as people who have expertise on acquiring forest products.” She points to the work of forest ecologist Herb Hammond, who co-founded the Silva Forest Foundation, a British Columbia-based organization that works with communities to plan human activities that use, protect, maintain, and – if necessary – restore ecosystem health and biodiversity. Dancer explains that Hammond figures out who lives in an area, maps their uses of the forest – with particular focus on locations used by First Nations for hunting, trapping, ceremony, and burial – and maps the ecosystem.

Once it’s mapped out, “you exclude all of those areas that already have a use,” Dancer explains. “Then you can think about going in and taking some trees [in other areas]. But then you do it selectively. You don’t just whack down everything.”