State of the unions

Militancy, “negative solidarity,” and fighting to win in Saskatchewan and Canada’s labour movement

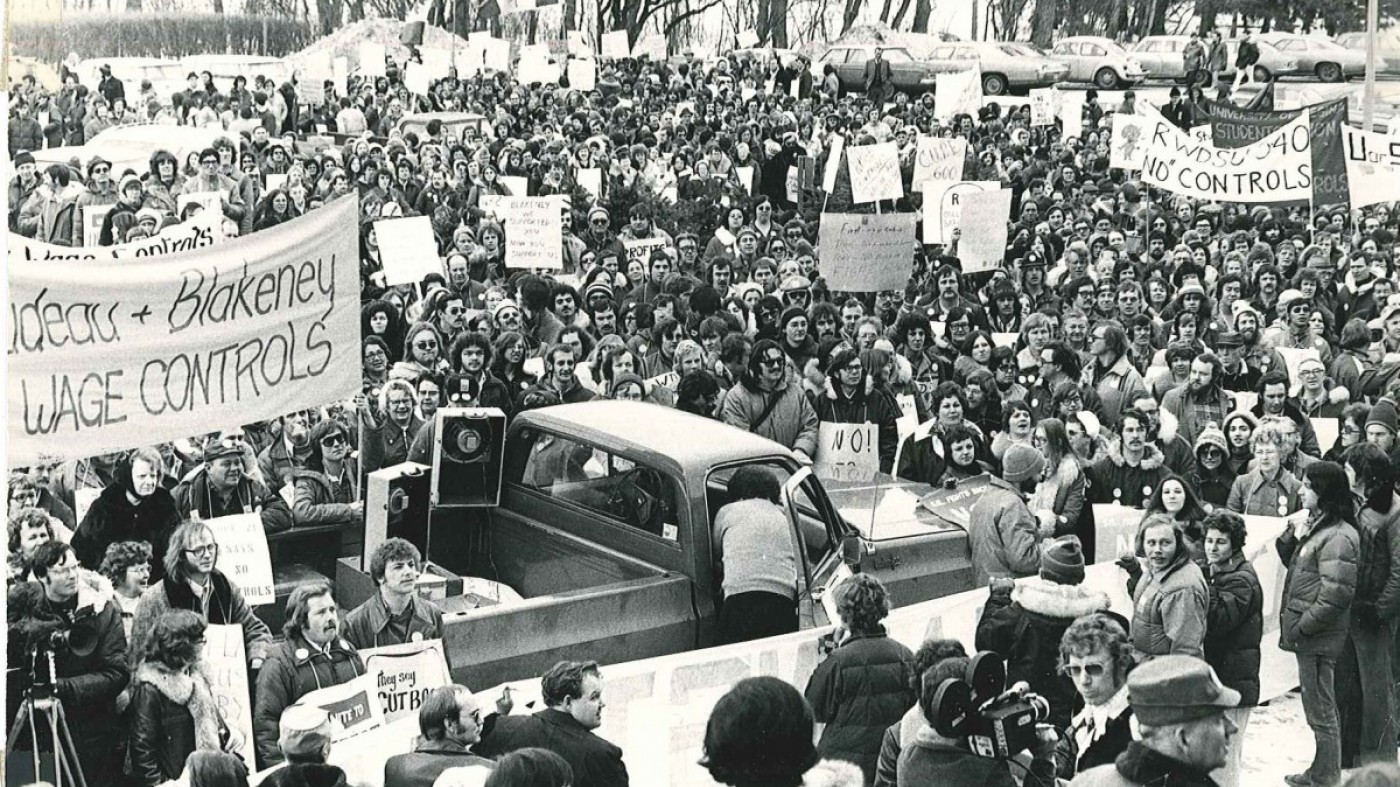

Workers rally against wage controls in Regina, Treaty 4 territory, on October 14, 1976. On the one-year anniversary of the introduction fo wage and price controls, more than one million workers across Canada staged a one-day national general strike called by the Canadian Labour Congress to protest wage controls and limits on free collective bargaining, imposed by the federal government and its provincial counterparts. In Saskatchewan, 28,000 workers participated in an illegal walkout in solidarity with the national action. Photo from the Briarpatch archives.

In January 2020, Paul Allen’s (not his real name) manager pulled him into the office and told him he was getting a raise. For Allen, a full-time student working for minimum wage in Regina, the raise was welcome, but there was a catch: it wasn’t really a raise at all. Instead, Allen’s union – the one that the company he worked for had never told him he was a part of – had made moves to cancel the certification. “They [the management] said ‘you’re now getting a pay raise,’” Allen says. “But they meant ‘you’re not paying your union dues.’ There was no real pay raise.” For Allen, the response from his co-workers was just as jarring as the message. “I was the only one who cared,” he says. Some of his co-workers were even “actively wanting to leave the union.”

Allen’s name and place of employment are being protected because he’s precariously employed and because the company – which did not confirm or deny that the loss of the union was framed as a raise or that workers were never told that they were part of a union – has a history of taking retaliatory measures. However, the concerns he raised tell a story that goes much deeper than one company and one union – it’s the story of the Canadian labour movement being brought to heel by restrictive labour laws and a media landscape that has spent decades undermining the collective power of workers through what University of Manitoba labour studies professor David Camfield calls a “never-ending barrage of anti-union messaging.”

“We can’t rule out that we have real political movements that vilify unions.”

And Camfield isn’t the only one who sees an anti-union culture at work. “Government, leaders, business […] all play a role in forming anti-union animus,” says Charles Smith, an associate professor in the department of political science at the University of Saskatchewan’s St. Thomas Moore College. “We can’t rule out that we have real political movements that vilify unions.” And although wealth has never trickled down further than the next generation of an already wealthy family, the attitudes of the ruling class have a way of imposing themselves on workers. “[Anti-union attitudes] filter through to the working class,” Smith says. There are elements of the working class that are anti-union.”

Allen agrees. “There’s an attitude of antagonism,” he says of his colleagues’ attitudes toward unions.

And perhaps we should not be surprised that workers feel alienated from labour unions and movements in this country. “In Canada, the big breakthrough for unions came through in the 1940s,” Camfield says. That means that Canadian workers today are almost as far removed from some of the most monumental wins in working-class history as those workers were from the end of the Industrial Revolution. “What we’re missing is victories that would inspire more people,” Camfield says. He adds that the sense of disillusionment many workers feel doesn’t end with the union. “We’re living in a time of falling expectations,” he says. “Lots of people have reason to think that work is getting worse,” he says, adding, “some of that anti-union sentiment comes out of a misplaced resentment when expectations are falling. Sometimes unions are not very helpful in the way they respond to that.”

That means that Canadian workers today are almost as far removed from some of the most monumental wins in working-class history as workers in the 1940s were from the end of the Industrial Revolution.

Camfield says that these falling expectations have led to what has been termed “negative solidarity.” He says that “if expectations are falling, instead of non-unionized workers looking toward what unionized workers have and thinking, ‘that’s a benchmark we should aspire to,’ instead there’s this idea of ‘I don’t have it, why should they have it?’” He says that unions have to recognize the role they play in changing the conversation. “When unions only go through the motions, if they aren’t fighting in a really militant way and giving it all they’ve got, then some workers will have negative experiences with unions and they talk to their co-workers, their relatives, and so on.”

Smith agrees that the kinds of hard-fought and hard-won battles that spurred trade unionism in the past play a powerful role in keeping workers engaged in the collective struggle. “When you’ve engaged in collective struggles together, those bonds are hard to break,” he says. But unions need to do more than just be there when the collective agreement expires. “Unions have to prioritize rank-and-file engagement, they have to think about ways to democratize their own internal structures, they have to be engaging with their workers on a weekly if not daily basis […] they have to be part of workers’ lives,” he says. “Unions need to internalize that. If [they] don’t do what [they]’re supposed to do – which is engage and empower the work force through democratic organization and a real sense of empowerment – then workers are going to start asking what the point of a union is.”

Allen says that when he first started talking to his co-workers about the union, he found that they didn’t understand what a union could do for them. One of his co-workers “complained about all these things, and when I said, ‘you know, the union can help with that,’ she just said, ‘I never thought about that.’” Allen wasn’t able to convince his co-worker – who claimed the union was taking 20 dollars per paycheque, an amount that could not be confirmed and that Allen says was not deducted from his pay – that the union was valuable enough to hold on to, but the exchange shows how much of the animosity toward unions is rooted in a poor understanding of what they can offer workers.

“Unions need to internalize that. If [they] don’t do what [they]’re supposed to do – which is engage and empower the work force through democratic organization and a real sense of empowerment – then workers are going to start asking what the point of a union is.”

Camfield says if unions want to increase engagement and counter negative press, they need to start appealing to workers who don’t hold a blue card or fall under their collective agreement. “If the political horizons of union leaders, union activists, don’t go beyond defending their own gains, if you only see unions essentially bargaining for their own members rather than having a broader vision of working-class politics, having a vision of what workers as a whole need, advancing the interests of workers as a whole and seeing unions as part of building a working-class movement, rather than just […] a bunch of bargaining units, then unions actually create conditions where they can be more easily marginalized and targeted by this kind of hostility and resentment.”

But changing the ingrained bureaucratic nature of unions may be easier said than done. “In the 1940s, unions fought and won certain gains in labour law, but those gains came with handcuffs,” Camfield says of the era that brought the labour laws we know today. Those laws gave Saskatchewan workers the right to join a union, required that that union be recognized by employers, and codified wage increases, shorter working hours, overtime pay, grievance procedures, and, for some, even vacation pay. But in spite of those steps forward, Camfield says “unions were really restricted by a tight web of labour legislation that restricted their right to strike, when they could strike, what they could strike for,” he says. “You can only go on strike at the end of the collective agreement when it expires, you can only go on strike for your own contract, you can’t go on strike to support anybody else, you can’t go on strike for political reasons,” he says, running through a laundry list of caveats. “The law reflects what workers are able to win in a particular moment in history,” and for Canadians, that means that “labour law is very favourable to employers.”

For people like Allen, working in places where the workforce is highly transitional and in which you have a small group of workers with very little leverage against a much larger employer, they’re going to have a difficult time getting – and maintaining – a union. “The way that labour law works in Canada, it really doesn’t help workers in those kinds of small workplaces,” Camfield says. In some European countries, workplaces like Allen’s are aided by “sectoral bargaining,” or a master contract for an entire industry, meaning that even those working for, say, a grocery store but who aren’t unionized are still covered by a collective agreement.

“The law reflects what workers are able to win in a particular moment in history,” and for Canadians, that means that “labour law is very favourable to employers.”

“Sometimes you hear people say, ‘well we need labour-law reform,’ but that begs the question […] because the real issue is how do you get the power to actually win that?” Camfield asks. In Saskatchewan, labour-law reform could come in the form of anti-scab legislation, which is currently in place only in Quebec and B.C.; card check, which would allow the labour board to certify a union if a certain percentage of workers sign a union membership card without a subsequent secret-ballot election; and first-contract arbitration, which would allow an arbitrator to impose an agreement when a company and a newly formed bargaining unit can’t concur on an first contract – which Smith says is “typically the hardest.”

But Camfield says that it takes a lot more than just knowing what needs to be done. “You could write the most rational, compelling arguments for different law and it will get you absolutely nowhere [without power],” he says. “More favourable labour law reflects a history of class struggle. Countries with stronger labour laws reflect situations where working-class movements were stronger.”

Smith says the answer to bigger wins could lie with illegal job actions – like solidarity strikes, where workers withdraw labour in support of other strikers; or wildcat strikes, like the 1999 Saskatchewan Union of Nurses (SUN) strike, which brought about significant wage increases for registered nurses. But he says illegal strikes come with caveats that can’t be taken lightly. “Some of the biggest historical gains for labour in Canada have been through illegal strike action,” he says. “The problem is that the risks are kind of ramped up when a strike is illegal.” The SUN wildcat strike, for example, inspired the Sask Party’s pursuit of regressive and enduring changes to Saskatchewan labour laws as soon as they took power in 2007 – changes that slap fines of $100,000 on a striking union, and $1,000 on employees who provide “essential services” and choose to strike.

“Some of the biggest historical gains for labour in Canada have been through illegal strike action.”

And Camfield says that there’s more to it than just job actions. “More favourable labour law reflects a history of class struggle,” he says. That means working-class people across the country need to be united in a drive for equity, and that sense of unity hasn’t reached a tipping point yet.

Both Camfield and Smith believe there are things that unions (and people who are pro-union but not necessarily part of a union bureaucracy) can do to bring change to the culture without putting anyone’s livelihood on the line. “In the short term, there are things that can be done, like trying to bring more democracy and militancy into unions that already exist. Trying to create workers’ centres that advocate for non-unionized workers,” says Camfield, pointing to the Workers’ Action Centre in Toronto as an example of an organization that strives to educate low-income and non-unionized workers about their rights in the workplace and to empower them to make the kinds of moves that will improve their working lives.

Smith points to smaller – but important – battles, like “getting more and better OH&S [occupational health and safety] in [a] workplace, getting an OH&S inspector. Those kinds of things empower workers in a way that unions have to be conscious of,” he says. “And the best unions are.”