The Fight for $15 in Saskatchewan

Fight for $15 campaigners outside the University of Saskatchewan. Photos courtesy of Catherine Gendron.

The minimum wage in Saskatchewan is a poverty wage.

The Saskatchewan Party government raised it by 10 cents on October 1, 2018, bringing it to $11.06 per hour, the second lowest in the country after Nova Scotia.

But 10 years ago, just after the Sask. Party was first elected, the province had the country’s second-highest minimum wage. Since then, while Saskatchewan has mostly pegged increases just over the rate of inflation, other governments have set their sights on a livable wage, spurred on by people-powered campaigns. In B.C., where there was a Fight for $15 campaign supported by the B.C. Federation of Labour, the NDP has bumped the minimum wage up a couple times from $10.85 to $12.65, with a plan of raising it to $15.20 by 2021.

Nick Day, an education student at the University of Regina, participated in the Fight for $15 and Fairness campaign while living in Kingston, Ontario, up until the summer of 2017. The legislative victory alone was impressive – Ontario’s Liberal government at the time raised the minimum wage from $11.60 to $14 per hour – but Day was “really invigorated by the organizing and building of a growing class consciousness in the province.” The group doorknocked, talked to people in malls and on the streets, held rallies, and developed a strong media and social media presence. When he returned to Saskatchewan in 2017, “not much was happening here,” Day says in a phone interview.

Two back-to-back provincial austerity budgets have been keeping activists busy fighting against the elimination of the Saskatchewan Transportation Company, against wage freezes, for libraries and children’s hearing aids, and more.

It might have something to do with the fact that two back-to-back provincial austerity budgets have been keeping activists busy fighting against the elimination of the Saskatchewan Transportation Company, against wage freezes, for libraries and children’s hearing aids, and more.

Then came January 1, 2018, when Ontario enacted a $2.40 per hour increase to the minimum wage – a major milestone that dominated media headlines across the country. Immediately, workers at some Ontario Tim Hortons saw their paid breaks, paid benefits, and other incentives slashed by franchise operators who sought to keep squeezing out profit. The tone-deaf response by bosses – who, in some cases, were the children of the chain’s founders – put the spotlight on the service industry, and the many workers in the industry who shoulder demanding, low-paying jobs.

Students signing petitions at the University of Regina.

Day and others, including students at the University of Regina, had just started a petition calling on the Sask. Party to raise the minimum wage to $15 per hour. About 15 people tabled by the busy Tim Hortons on campus on January 19, 2018, and others were stationed in and around the Cornwall Centre in downtown Regina, which also has a Tim Hortons inside.

“The reception we got on campus was overwhelmingly positive,” says Day. “Maybe one in 20 or 30 people had something dismissive to say, [but] the rest were positive.”

In Saskatoon, students and other organizers were collecting signatures on the same petition that day, around the Midtown Plaza. Students at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon have also tabled on campus a few times.

“The people of Saskatchewan are clearly on side with this,” says Day. “The Sask. Party position is way out of line with where Saskatchewan people land on the issue.”

The petition drive in January quickly racked up over 1,200 signatures, but the effort has stalled since then. Both NDP leadership candidates, Trent Wotherspoon and Ryan Meili, campaigned on a phased-in minimum wage increase to $15 during the March leadership race. But since Meili won the race, the NDP hasn’t built grassroots support to push the issue much further.

Petitioning at the University of Saskatchewan, in Saskatoon.

The Saskatchewan Federation of Labour (SFL) has long supported livable-wage campaigns. Its website hosts a petition calling on the Sask. Party to implement “a rapid phase-in to $15 per hour.”

“The [SFL] believes all workers should be compensated fairly for their labour,” says outgoing SFL president Larry Hubich in an email to the Dispatch. “Having a job should lift people out of poverty – not keep them in it. A living wage not only allows workers to make ends meet, it also stimulates local economies, creates more jobs, and strengthens communities.” Hubich encourages people to take to the streets, join campaigns, and contact politicians. He stresses the importance of supporting workers who are trying to form unions, as this will help increase workers’ wages.

The SFL, which saw its membership shrink by about 10 per cent when Unifor disaffiliated in January 2018, has not dedicated resources, like staff time, toward campaigns to fight for a higher minimum wage*. Few unions in the province have, and some – like the Saskatchewan Joint Board of the Retail, Wholesale Department Store Union (SJB-RWDSU), of which Briarpatch staff are members – say they are not leading their own campaign, but would get on board with one led by the SFL. Service Employees’ International Union-West (SEIU-West) provided some support, like helping to create a campaign website.

Day says “there is great organizing potential” around the fight to raise the minimum wage, but that there is “essentially no institutional support.” Unlike in Ontario, there is no workers’ action centre in Saskatchewan able to dedicate staff time to the campaign.

Not just about minimum wage

Nairn MacKay has worked jobs near minimum wage, been on social assistance, and worked for social services. Today, she helps coordinate anti-poverty groups and campaigns, including Poverty Free Saskatchewan.

MacKay says she supports liveable-wage campaigns, but points out that increasing the minimum wage isn’t a panacea for poverty. She worries that livable-wage campaigns may assume “people working at or near minimum wage are working full-time hours,” she says. That often isn’t the case, though – many minimum-wage jobs are part time, and even full-time minimum-wage jobs are often short-lived. This means people are going on and off of social assistance throughout the year, and possibly collecting employment insurance (EI) if they qualify. Campaigns for only a livable wage may not actually address the type of poverty and precarity faced by workers who aren’t working full time all year round. Programs like social assistance and the recently slashed Saskatchewan Rental Housing Supplement, for example, factor in as important ways that low-wage workers make ends meet.

In Ontario, the Fight for $15 and Fairness campaign’s demands included paid sick days, fairer scheduling, removing barriers to unionization, and stronger labour standards. Neither the SFL website nor the Fight for $15 petition circulated in Regina and Saskatoon specifically called for changes to working conditions other than an increase in the minimum wage. Few minimum-wage campaigns anywhere have called for anti-poverty supports that apply to people who are not involved in wage work, like increases to social assistance.

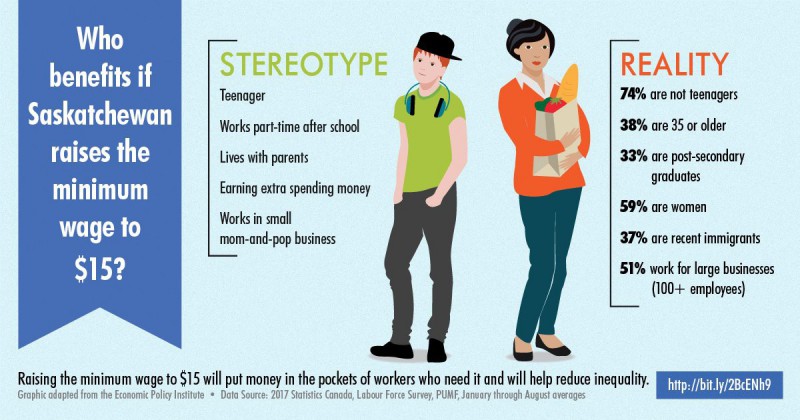

Graphic courtesy of Fight for $15 Saskatchewan, adapted from the Economic Policy Institute. Data Source: 2017 Statistics Canada Labour Force Survey, PUMF, January through August averages.

Some of the language and phrases around livable-wage campaigns can be harmful as well, McKay says. You’ll often hear, “Nobody who works should be in poverty,” says MacKay. “No,” she responds, “Nobody should be in poverty. An adequate standard of living is a fundamental human right.” It raises the question of how a campaign that fights for a higher minimum wage can avoid a “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” mentality that idealizes wage work as the solution to poverty.

But this may be particularly difficult in Saskatchewan. An Angus Reid survey of people across Canada, published this summer, asked respondents to choose between whether there should be “more public support for the poor, the disadvantaged and those in economic trouble” or “more emphasis on a system that rewards hard work and initiative.” Saskatchewan had the highest rate of response for the option of wanting to see a system rewarding hard work and initiative. The neighbouring Prairie provinces had the next highest rates of response for that option.

So what’s next?

The campaigning in Regina and Saskatoon in January showed there is desire and support for a livable wage, but also a lack of coordination.

The Ontario campaign wasn’t won because of former premier Kathleen Wynne’s altruism. There was a major grassroots effort, institutional backing from the Ontario Federation of Labour through its Make It Fair campaign, and a mass of people who were increasingly well informed on the issue and willing to speak out – to the extent that the government could no longer ignore the pressure.

“The activist spaces [in Saskatchewan] have become incredibly small,” says MacKay. “We need to reach out to and build with people who identify as not political.”

*UPDATE, Nov 6, 2018: The Saskatchewan Federation of Labour has announced it is holding education and organizing meetings in Saskatoon and Regina on “How to win the Fight for 15.”

UPDATE, Nov 6, 2018: The article originally stated that Poverty Free Saskatchewan is a newly created organization. It has been corrected as the organization has in fact existed for several years.